Governments step up their actions against sports corruption

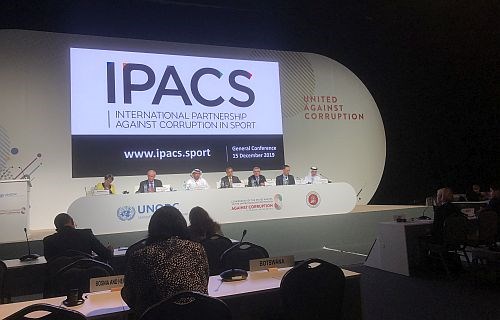

General Conference of the International Partnership Against Corruption in Sport, Abu Dhabi National Exhibition Centre (ADNEC). Photo: Play the Game

Imagine that you were the leader of a movement stained by numerous corruption cases, and that some of your closest allies were under criminal investigation around the world. Would you expect to be invited to speak to the governments of the world? And if you got that invitation, how would you address them?

Thomas Bach, the powerful leader of the International Olympic Committee, wasted no time apologising for the past or the present when he opened the second high level meeting of the newly established International Partnership Against Corruption in Sport (IPACS) on Sunday 15 December 2019 in Abu Dhabi.

While praising the IOC’s own reform programme Agenda 2020 for having revolutionised the way the Olympic movement works, he presented the IOC as the leader of the fight against corruption in sport to the around 45 governments present, and a similar number of sports leaders and people from UN organisations:

“As the leader of the Olympic Movement, the IOC is calling on all other stakeholders to follow our lead when it comes to setting a new standard with regards to good governance and fighting corruption,” Thomas Bach said.

“We know we cannot win this fight on our own. We need the support of governments when it comes to anti-corruption legislation and law enforcement. This is why IPACS is so important.”

Growing concern amongst governments

IPACS grew out of a meeting on sports corruption called by the then British Prime Minister David Cameron in May 2016. It wishes “to bring together international sports organisations, governments, inter-governmental organisations, and other relevant stakeholders to strengthen and support efforts to eliminate corruption and promote a culture of good governance in and around sport”.

Even if the logotype of IPACS is discreetly adorned with the colours of the five Olympic rings, it is not yet clear whether governments will heed Thomas Bach’s call to accept IOC leadership. Some might want to put themselves in the driver’s seat.

In the diplomatic setting of a United Nations’ meeting, the IOC receives a lot of praise, but when the microphones are turned off or in closed meetings, the tone is more sceptical.

A growing number of governments are concerned with the proven corruption cases and poor standards of governance in the international sports federations, and with the current criminal investigations into people who just a few years ago were prominent IOC leaders in the circle around Bach:

IOC Vice-President Patrick Hickey from Ireland, former head of the Rio 2016 Olympics, Carlos Nuzman, the head of the Asian Olympic Committee sheikh Ahmad Al-Sabah from Kuwait, and, last but not least, the former athletics president Lamine Diack from Senegal who will soon stand trial for bribery in France. To name just a few.

European governments introduce regulations

Days before the Abu Dhabi conference, at a closed meeting in Finland among leading officials from EU sports ministries, the trend was clear: An increasing number of countries have introduced or are preparing to introduce regulations that link public grants to sport to good governance requirements.

”We all respect the autonomy of sport, but we spend millions of tax payers’ money and we must demand not only words, but action from sports organisations in delivering integrity, transparency and accountability. They must live the values of sport,” it was said.

Two governments that were not represented in Finland, followed that trend at the Abu Dhabi meeting. The Senior Chief of Governance & Compliance in Japan Sport Council, Toshiyuki Okeya, explained how his institution – which is set up, but not run by the government – will define stricter rules for conflicts of interest.

The sport council already requires that all sports federations that are part of an umbrella organisation carry out self-assessment with regard to governance, and the council follows up checking their compliance.

“When we find irregularities, we decrease the funding or, in the worst case, demand the money back,” Okeya said.

New governance code in the UK

From the UK government, the head of international sport, Hitesh Patel, told how a new governance code had strengthened independence and transparency, introduced term limits, made the governing board the supreme decision-making body, and promoted gender and ethnic diversity.

“In the government funding we issue no blank checks. Public funding is a privilege, not a right, and we have a duty as go to safeguard public investment,” he said.

When questioned how sports organisations had reacted to this seeming attack on their autonomy, Hitesh explained that the government still stayed out of the daily business of sport:

“We have set up wider governance frameworks. We monitor their compliance, but don’t directly intervene. If they don’t implement it, they won’t receive funding, and it is amazing how they fall into line.”

Four task forces

The meeting in Abu Dhabi was the first time that all nations of the world were invited to comment on and make commitments to the work of IPACS. It was held in connection with the General Conference of the United Nations Organisation on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) to allow a big number of countries to take part.

The main purpose was to inform the countries of the way IPACS operates through four task forces in areas with a high risk of corruption:

1) The awarding of public contracts in relation to major events

2) The selection of host countries, cities and venues for major events

3) Compliance with good governance principles, and

4) Cooperation between criminal justice authorities and sports organisations

All task forces are still at a stage where they are analysing their areas and discussing tools and standards. All of them are still to come up with solutions.

However, openness and transparency in all transactions stood out as a requirement for the handling of major sports events.

Among those stressing this point was the French expert Hervé Rey, who has led a study commissioned by the IOC and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD):

“It is more important than ever to have open competitive tender. It is more important than ever to have good governance in the event organisation. And it is more important than ever to have a solid evaluation process,” he said, adding that this would also allow event organisers to get better value for money.

“There is today a lack of efficiency in the public procurement in the life cycle of sports events.”

Failure in people

The head of anti-corruption in the Italian Olympic Committee (CONI), Marco Befera, found after 13 years of work that corruption was not a failure in systems and controls, but in people.

“We have to focus on soft control, trust, the ethical climate in the organisation. Like the weather, this climate can influence human life,” he said while raising the question of how to foster such a climate:

“There is a risk of window dressing policies or cross your fingers strategies. Our experience is that full disclosure and flow of information can fulfil both the purpose of preventing corruption and having a collateral effect on the behaviour of organisations.”

Befera recommended designing software and procedures that disclose all transactions, including on the website of the organisation, with due respect for privacy laws:

“We have to disrupt a system where only the procurement director knows what is going on. We base our efforts on a red flag system where we gather periodic information about irregularities, every time something is not going as expected. It is not a proof of fraud, but an early warning system.”

Handling conflicts of interests

Another overarching theme was how to understand what constitutes a conflict of interests. A good personal relation does not necessarily lead to a conflict of interests, but there are particular risks in small federations with “a tight-knit community”, as it was highlighted by Martin Damsbergs from the International Bobsleigh and Skeleton Federation (IBSF).

The short and compact winter sport calendar required effective use of funds:

“We run a great risk if we run processes by tradition and through good personal and professional relations. We have very limited competition in the market, both for the delivery of sledges and of venues. Some consider we are not big enough to put procedures in place, but concerted practice is just as dangerous to effective procurement as corruption.”

IOC needs change of culture

Even in an organisation on a very different scale, it could be difficult for members to understand what “conflict of interest” means, said Pâquerette Girard Zappelli, IOC’s Chief of Compliance and Ethics:

“We need to move from having regulations over to total acceptance. We must change the culture, and that is probably the most difficult task,” she said, pointing to a future where IOC members would be more active:

“I would like to see a procedure where we have a permanent disclosure of interest, managed electronically day by day with each member’s self-assessments of risks.”

Pâquerette Girard Zappelli recognised that the IOC’s new procedure for identifying Olympic host cities – through discussion with selected cities rather than open bidding processes – could appear less transparent. But she argued that a closer dialogue between the IOC and the candidates could also improve the understanding of the risks of corruption.

This should not just happen in order for sport to learn lessons, but also be a way to “answer to the level of request from the general public”. She referred to the surveys and referendums that came out negative for the Olympic Games when local citizens where asked if they wished to pay for hosting these:

“The public was not challenging the decisions by governments to host the Olympics 20 years ago. Now they do, and they are right, they are totally right to challenge this. So we must be better to introduce procedures that ensure the right balance of interests, and consider the national public perception.”

50 governance recommendations

The Abu Dhabi meeting revealed some new initiatives from IPACS that are likely to lead to discussions.

IPACS’ task force 3 is currently setting up a governance benchmarking system with 50 recommendations and guidelines for implementing them. These recommendations will include requirements known from the anti-corruption standards already defined by organisations like the OECD, the UNODC and the Group of States against Corruption (GRECO). And it should be designed to be applied both at the national and international level.

Officially, this new effort is based by the Olympic movement’s own benchmarking system, carried out by the Association of Summer Olympic International Federations (ASOIF).

This could lead to a battle between the Olympic federations, who are used to hide their results in the anonymity of the ASOIF reports, and the public sector that will need to see names, if the public grants are linked with good governance achievements.

At the IPACS meeting, the coordinator of the internal Olympic benchmarking, promised “greater transparency about the results” when the third round of benchmarking is presented in April 2020. It is still unclear to which extent the lid will be lifted.

Access to information from police and prosecutors

Another new initiative from IPACS is a task force 4 which will stregthen “cooperation between criminal justice authorities and sports organizations”.

Pâquerette Girard Zappelli stressed that the IOC needs access to the facts in order to sanction sports leaders with internal disciplinary measures:

“We need more evidence to make sure sanctions are justified, so they can stand up in an appeal. The burden of proof in CAS [Court of Arbitration for Sport], is not the same as for criminal justice. But when the evidence is not enough for a criminal sentence, we end up without neither criminal nor sports justice.”

She recognised it would be difficult for police and prosecutors to hand over information to a private entity like the IOC, and Sebastian Bley, head of anti-corruption in Interpol, confirmed that difficulty:

“We have a good cooperation with sport at the strategic level. But when it comes to exchange of personal data, this is regulated by laws. An officer must have a basis for sharing the information, otherwise he runs the risk of committing a crime himself,” Bley said.

He found that the ball was not only in the court of governments, but also in the court of sports:

“Sport is independent, but it must consider to which extent it is willing to share information, so justice can be carried out in public courts.”

Bley ended his statement with a warning:

“We hear about the impact of criminal organisations. On the other hand we don’t see that many criminal investigations, and also not many convictions. There is a very big dark field that should be lightened up, and the task force could motivate governments to consider how the relevant stakeholders can exchange information.”

NB! Neither Play the Game nor any other sports-related organisation outside the Olympic family was invited to the IPACS meeting. Play the Game got access only because we were granted a seat in the Danish delegation.