Corruption is blocking the power of sport

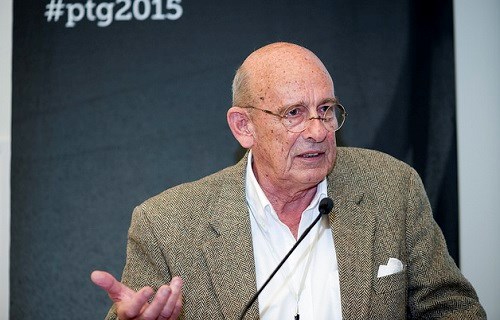

Bob Munro, founder of the Mathare United youth project in Kenya spoke about how to use the power of sport more actively. Photo: Thomas Søndergaard/Play the Game

27.10.2015

By Steve MenaryDeborah Unger, the manager of Transparency International’s (TI) Rapid Response Unit, kicked off the session by detailing TI’s work in sport and the forthcoming Global Corruption Report on sport, which Unger is editing.

TI first began looking at sport in 2008 and produced a working paper two years later, followed by a map for FIFA reform in 2011.

“That was pretty much not taken on board by FIFA,” sighed Unger. “That is why we are joining with New FIFA Now in wanting an independent reform committee as we don’t think FIFA has what it takes to carry out root and branch reform.”

TI has also begun working with sports fans, notably in the Republic of Ireland. Here, TI is working with the You Boys In Green supporter group, which was angered by the lack of transparency over allocation of away tickets for Irish international matches and the 5 million euro payment from FIFA after the team was eliminated from the 2010 World Cup by France after a handball by Thierry Henry.

All these initiatives are, says Unger, part of a dialogue on sport that TI wants to continue with the forthcoming report. “We don’t have all the answers,” admitted Unger.

From prosecution to defence

Bob Munro, chairman of the Mathare United youth project in Kenya, has written the foreword to the report and been campaigning against corruption in the African country for 15 years but he provided a more encouraging follow-up.

“I have often been here as the witness for the prosecution,” said Munro. “Now, I am here as a witness for the defence.”

In a passionate defence of the achievements at Mathare and its role in reforming the Kenyan football league, Munro argued that a league owned by its clubs worked against corruption.

Pointing to the English Premier League, the German Bundesliga, the Premier Soccer League in South Africa and the Kenyan Premier League as positive examples, Munro said: “As soon as you have a league owned and run by clubs, you have 20 auditors and you have shareholders.”

However, Munro concluded by saying: “A lot more can be done. We have to use the power of sport more actively than we do now.”

The failure of sport and a mega-event to instill a sporting culture in India was the subject of the presentation by Indian journalist Murali Krishnan, who argued that the 2010 Commonwealth Games had been a failure despite an investment of USD 4 million.

‘Indian sport is a pile of rubbish’

After showing the audience a stream of images of 2010 stadia in poor repair, Krishnan showed refuse outside a venue and asserted: “Indian sport is a pile of rubbish.”

He added: “There has not even been tentative steps to build a sports culture.”

Football, badminton and Kabaddi had shown “some encouraging signs” of development in a country with a 1.2 billion population but in a scathing presentation on the state of Indian sport, Krishnan said: “Most sports are run by politicians who are clueless.”

“I am very pessimistic that a vibrant sports culture can ever be initiated in India, let alone allowed to grow.”

Russia has a more vibrant sports culture but Sergey Yurlov from the Russian National Union of Sports Lawyers put across a coherent argument for a sporting ombudsman, which he christened Rossportnadzor, as the ultimate body for sports’ disputes in his country. “There is no recourse to ordinary courts over disputes,” said Yurlov.

Need for revolutionary change

Journalist and former International Handball Federation (IHF) official Christer Ahl detailed the latest instance of corruption in the IHF, which he described as a “despotic regime”.

Mr Ahl said that he was “sceptical” of allowing self-reporting at sports federations such as the IHF and FIFA. “They don’t need autonomy, they need revolutionary change imposed upon them,” said Ahl.

The session concluded with a potent example of football’s need for revolutionary change to improve its lack of credibility as Umaid Wasim, a journalist from Pakistani newspaper Dawn, detailed multiple instances of money from FIFA’s Goal programme going unspent.

The Pakistan Football Federation (PFF) had, Wasim said, been awarded eight separate Goal grants but only one of these projects, the PFF’s headquarters in Lahore, had been completed.

Wasim gave other instances of malpractice at the PFF, including the president holding meetings in his own home that had been sanctioned by the Asian Football Confederation, and concluded that organisations such as TI could help introduce greater transparency in his country.