Most sports federations fail to meet basic principles of good governance

Led by FIFA, international sports federations have been regular subjects in newspaper reports on corruption, abuse of power and lack of transparency and democracy. But how well are the international federations actually doing – individually and as a whole – if they are evaluated on a number of well-established indicators of good governance in organisations?

This is one of the key questions behind a new study focussing on the international federations representing 35 Olympic sports. The study is based on the Sports Governance Observer – a governance measurement tool recently developed by Play the Game and the University of Leuven in co-operation with a number of partners (see box).

The first preliminary results from the ongoing study depict an international sports community with severe challenges in living up to organisational standards of good governance, judged so far by their performance against 6 individual indicators out of a total of 38.

According to Arnout Geeraert, who is a senior research fellow at the University of Leuven and working on the study on behalf of Play the Game as well, the first results not only demonstrate large variations between the federations, they also show that each individual federation scores very unevenly:

“Some score high on some indicators and low on others. This shows that there may be a will in some organisations to work with governance, but also that some federations do not know which processes are most important to address. So they need to be informed better. Additionally, we also see that most federations score poorly on some of the very important indicators. This suggests that there is a more general governance challenge in international sport.”

Few or weak audit and ethics committees

A typical problem is that very few federations have established independent audit and ethics committees with sufficient authority and power to execute efficient financial controls, conduct risk management and to monitor the application of an ethics code if such is present at all.

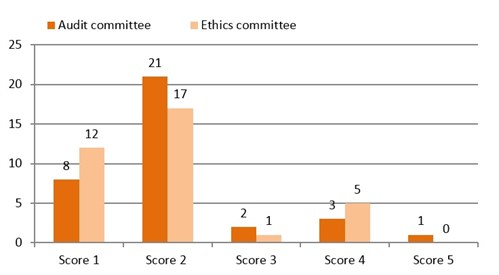

The study shows that eight federations do not have an internal audit committee and 12 fail to have an ethics committee, scoring only 1 in a scale of 1 to 5. Moreover, the majority of the remaining federations are not doing much better (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The organisation has internal audit and ethics committees (n =35)

Only a few federations have robust and independent audit and ethics committees. Most federations score a 2, indicating that their audit and ethic committees are not working independently and have very unclear or limited competences. The single federation scoring 5 is FIFA.

Only a few federations have robust and independent audit and ethics committees. Most federations score a 2, indicating that their audit and ethic committees are not working independently and have very unclear or limited competences. The single federation scoring 5 is FIFA.

On average, the federations score a modest 2.09 (audit committee) and 1.97 (ethics committee) in the system, where a score of 1 represents ‘not fulfilled at all’, 2 means ‘weak’, 3 is ‘moderate’, 4 is ‘good’ and 5 is ‘state of the art’.

According to Arnout Geeraert, these results indicate that most federations do not have systems in place that can control the management of the organisations in a sufficient way.

“This is a severe issue. In most federations, there is a need for more robust audit committees, good codes of ethics and well-functioning, robust ethics committees. If they function well they can be really powerful tools decreasing the risk of corruption and other unethical behaviour. So these two indicators are really important in organisational structures,” Geeraert says.

“However, one of the biggest problems – and this why some federations score so low – is of course the fact that some ethical committees are not able to judge on the behaviour of senior officials. In many cases they even need the consent of the president or the executive committee to start investigations.”

No term limits in most federations

The federations come out with even lower scores when they are evaluated on the issue of term and age limits for senior officials.

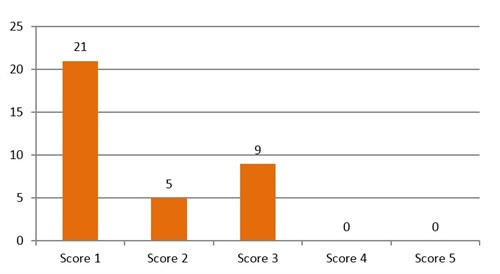

A clear majority of 21 international sports federations have no limits whatsoever and none of the federations score a 4 or 5 (Figure 2). On average, the federations score a very low 1.66.

Figure 2: The organisation’s elected officials have a term limit (n = 35) Most federations do not have term limits in place, while some operate with age limits (score 2) or term limits only comprising a few positions or allowing senior officials more than 8 years in office (score 3).

Most federations do not have term limits in place, while some operate with age limits (score 2) or term limits only comprising a few positions or allowing senior officials more than 8 years in office (score 3).

According to Arnout Geeraert, the lack of term limits in many international sports federations increases the risk of adverse power accumulation, abuse of power, lack of accountability and a weak internal democracy.

“With seniority comes power. We know that people who hold office have a higher chance of being re-elected, but if it is for sure that a certain person will be re-elected, there is a risk that the members of the organisation will lose interest in the democratic processes and the senior officials will lose touch with their own voters,” Geeraert argues.

The lack of term limits has led to a number of presidents sitting in office for many years. In 2013, a the final report from the AGGIS project leading up to the Sports Governance Observer showed that all of the presidents of the international Olympic sports federations had been in office for no less than 14 years on average.

Arnout Geeraert mentions Sepp Blatter’s 17-year-long presidency at FIFA – preceded by 17 years as a Secretary General - as a textbook example of how power can concentrate around one person over a number of years. Conversely, some will argue that term limits will drain an organisation of its important knowledge and experience. But Geeraert disagrees that this is relevant in most Olympic sports, which can uphold a relatively strong organisation, partly funded by Olympic revenues from the IOC and, in some cases, also substantial commercial income streams.

“Such organisations will not lose irreplaceable expertise by letting a president or another senior official go after eight years. There will be somebody else willing and able to take over in an international sports federation. But there is culture of staying for a very long time in many sports federations, so this is difficult to change, although it is a very big problem,” he says.

Regular and frequent general assemblies

The international sports federations are doing better when it comes to the three remaining governance indicators out of the six described here.

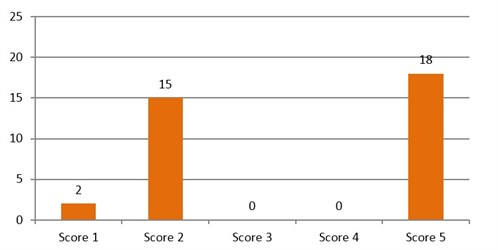

Most notably, 18 out of 35 federations get a maximum score of 5 in regard to how often they hold a general assembly, which reflects that they are not only meeting at least once a year, but they also have clear procedures outlined in their statutes for convening emergency and special meetings.

On average, the federations score a decent 3.49, but as Figure 3 shows, the picture is highly polarised with many federations scoring a modest 2, as they have biannual general assemblies, and two federations meeting even less frequently, scoring only 1.

Figure 3: The organisation’s general assembly meets at least once a year (n =35)

The two federations scoring 1 are the International Boxing Association, AIBA, and International Swimming Federation, FINA.

The two federations scoring 1 are the International Boxing Association, AIBA, and International Swimming Federation, FINA.

According to Arnout Geeraert, meeting face-to-face regularly allows members better opportunities to keep an organisation's management and senior officials accountable.

“Meeting once a year is an absolute minimum. Especially the Olympic sports federations that receive funding from the IOC should be able to do that. But there are still a relatively large number of federations that score badly against this very basic indicator.”

Insufficient transparency

The same issue of accountability is relevant with annual general activity reports and externally audited financial reports.

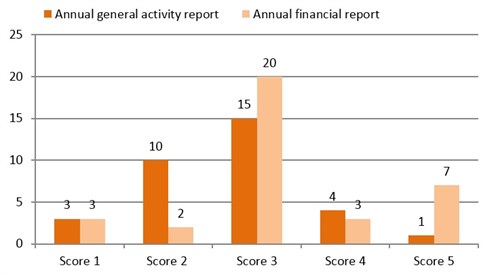

However, the results are also mixed in this area, with few federations scoring high, especially when it comes to publishing financial reports, while others are performing in the midrange area or even poorly (see Figure 4). In total, 5 in 33 federations make their annual general activity report publicly available while 10 publish a financial report online. On average, the federations score 2.70 on activity reports and 3.26 on financial reports.

Figure 4: The organisation publishes its annual general activity report and an externally audited annual financial report on its website (n = 33, n = 35) Data concerning the general activity reports is only available from 33 out of the 35 federations. The International Rugby Board is the only one to score 5, which reflects that a comprehensive and accountable activity report is published online. More federations score 5 on the financial report, which indicates that an externally audited annual financial report is made public online as well as reports from the past 3 years.

Data concerning the general activity reports is only available from 33 out of the 35 federations. The International Rugby Board is the only one to score 5, which reflects that a comprehensive and accountable activity report is published online. More federations score 5 on the financial report, which indicates that an externally audited annual financial report is made public online as well as reports from the past 3 years.

According to Arnout Geeraert, the moderate scores reflect that many federations only provide the reports to their member circle.

“That is a good start and you get a moderate score for that. However, there are many other stakeholders in sport, and if more actors are able to monitor the organisations, it will decrease the likelihood of unethical behaviour. Said in a black and white way: If you know that more people are watching you, you will have less incitement to behave unethically.”

Geeraert also criticises the quality of some of the published reports.

“The activity reports in particular sometimes look more like publicity folders than a really critical self-evaluation, and that is a problem. Your member federations are the first ones to hold you to account, but if you do not provide them with a complete general or financial report, they are simply not able to evaluate your activities on a yearly basis.”

Who comes out on the top?

The total combined scores of the six indicators show significant differences between the federations and their general governance level.

Among the lowest scoring are federations like the International Boxing Association (AIBA), the International Swimming Federation (FINA), the International Volleyball Federation (FIVB), the International Canoe Federation (ICF) and the International Biathlon Union – all with an average score against the six indicators of around or just below 2.

At the top-end are federations like the International Rowing Federation (FISA), the International Federation for Equestrian Sports (FEI), the International Sailing Federation (ISAF), the International Rugby Board (IRB) and the International Cycling Union, with average scores of around 3.5.

And the best performing federation of all? It is none less than FIFA... The very symbol of all the governance challenges that many international sports organisations are facing gets an average score of 4. Apart from the indicator on term limits where FIFA only scores a very low 1, the international football federation scores 4 or 5 against all indicators.

How can that the currently most scandalous and corruption-ridden organisation in international sport come out on top?

According to Arnout Geeraert, it is less paradoxical than it may sound. In the case of FIFA, the relatively good performance should be seen in relation to the reform process the international football organisation has been forced to initiate, which has – at least formally – created better governance procedures in the organisation. This could also be the case for an organisation like the UCI, which is also scoring decently.

“FIFA and UCI have taken some modest but good steps in the right direction, which is reflected in the scores. Secondly, FIFA is a huge global organisation, and organisations of that size really need state-of-the-art governance structures because the risks are higher,” Geeraert explains.

Not the whole picture

Finally, and very importantly, the Sports Governance Observer and its indicators do not say anything about how corrupt or mismanaged an organisation is. In principle, a very low scoring organisation could be clean-cut, while a high scoring organisation may be sinking in a swamp of corruption.

According to Geeraert, the Sports Governance Observer nevertheless gives some basic indicators on how well equipped an organisation is to support and underpin good governance procedures, minimising the likelihood of corruption, abuse of power and other examples of poor governance.

However, the governance principles do not stand alone. Organisational cultures, as well as social and political structures, are also important factors. As he concludes:

“There is no guarantee that you can stop people who want to behave unethically, but with all the right organisational structures in place you can increase the likelihood of good governance.”

Arnout Geeraert will present the main results of the study at the Play the Game 2015 conference in October, taking place in Aarhus, Denmark. Leading up to that, playthegame.org will publish more articles with preliminary results from the study on governance in international sports federations.

While agreeing with Geeraert that international federations such as FIFA need excellent structures. Unfortunately, while the mechanical components, e.g. committees, compliance are regularly measured and understood, the people (directors and executives) are not. If the people are no good, all the regulation, compliance, good governance standards and committees in the world, will not stop an organisation from being poorly governed with the ensuing outcomes, poor decision making corruption, etc.

It is only when the behavioural governance of the board and executive is reviewed, measured, detailed and the recommended actions for change implemented, will we see change in the way organisations are governed and the resulting change in outcomes and performance. It is the performance of the board and executive within the governance environment of the 'third team' that leads to higher, more accountable standards of governance being achieved.