Few clubs dominate Europe’s football leagues: Champions League Diversity Index 2019/20

(Updated 2 July 2019)

The same clubs won their titles in more than half of UEFA’s members last season as the UEFA Champions League slowly evolves into a closed shop at all levels.

The winners of Europe’s leading five leagues – England, France, Germany, Italy and Spain – all retained their titles last season, and so did the reigning champions in another 23 countries across Europe.

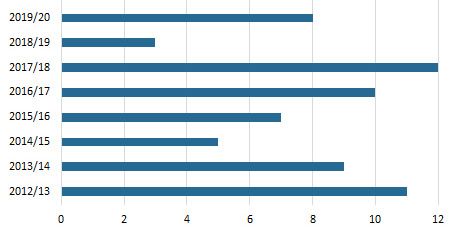

While the number of new debutants entering the UEFA Champions League (UCL) in 2019/20 has risen to eight compared to just three last year (see figure 1), no club that won their title for the first time is likely to qualify for the lucrative group stages.

Figure 1: New Champions League entrants

Italy’s Atalanta go straight into the UCL group stage despite only finishing third in Serie A, while Krasnodar enter at the penultimate qualifying round but finished in the same position in the Russian Premier League.

With only six UCL group places available to qualifiers, Austrian Bundesliga runners-up LASK Linz have only an outside chance of joining Red Bull Salzburg in the group stages in their debut season.

The only club to actually win their league last season and have even a remote possibility of qualifying for the group stages are Piast Gliwice after winning Poland’s Estraklasa in 2018/19. The other UCL debutants - Latvia’s Riga FC, Ararat Yerevan of Armenia, Feronikelli of Kosovo and Georgia’s Saburtalo Tbilisi – are all highly unlikely to qualify for the group stages.

Fewer clubs qualify for Champions League

On the whole, the number of clubs from Europe’s main leagues that are qualifying for the UCL is shrinking as Play the Game’s annual Diversity Index shows.

England, France, Germany, Italy and Spain are amongst the least diverse countries as a handful of the same clubs often take up the same places in the UCL (see table 1).

Table 1: Play the Game Champions League Diversity Index 2019 (higher index score = less diverse)

|

Country |

Appearances |

Clubs |

Index |

|

Greece |

50 |

4 |

12,50 |

|

Ukraine |

46 |

4 |

11,50 |

|

England |

90 |

10 |

9,00 |

|

Croatia |

27 |

3 |

9,00 |

|

Scotland |

35 | 4 | 8,75 |

|

Portugal |

59 |

7 |

8,43 |

|

Spain |

94 |

12 |

7,83 |

|

Serbia |

23 |

3 |

7,67 |

|

Holland |

53 |

7 |

7,57 |

|

Belgium |

45 |

6 |

7,50 |

|

Italy |

86 |

12 |

7,17 |

|

Turkey |

47 |

7 |

6,71 |

|

Luxembourg |

24 |

4 |

6,00 |

|

France |

70 |

12 |

5,83 |

|

Germany |

81 |

14 |

5,79 |

|

Czech Rep. |

40 |

7 |

5,71 |

|

Russia |

50 |

9 |

5,56 |

|

Cyprus |

25 |

5 |

5,00 |

|

Austria |

35 |

7 |

5,00 |

|

Malta* |

23 |

5 |

4,60 |

|

Lithuania |

23 |

5 |

4,60 |

|

Bulgaria |

23 |

5 |

4,60 |

|

Slovenia |

23 |

5 |

4,60 |

|

N Ireland |

23 |

5 |

4,60 |

|

Wales |

23 |

5 |

4,60 |

|

Moldova |

23 |

5 |

4,60 |

|

Israel |

27 |

6 |

4,50 |

|

Switzerland |

38 |

9 |

4,22 |

|

Norway |

29 |

7 |

4,14 |

|

Denmark |

31 |

8 |

3,88 |

|

Latvia |

23 |

6 |

3,83 |

|

Estonia |

23 |

6 |

3,83 |

|

Poland |

26 |

7 |

3,71 |

|

Romania |

34 |

10 |

3,40 |

|

Armenia |

23 |

7 |

3,29 |

|

Iceland |

23 |

7 |

3,29 |

|

Belarus |

23 |

7 |

3,29 |

|

Albania |

23 |

7 |

3,29 |

|

Faroes |

23 |

7 |

3,29 |

|

Andorra |

13 |

4 |

3,25 |

|

Gibraltar |

6 |

2 |

3,00 |

|

Ireland |

23 |

8 |

2,88 |

|

North Macedonia |

23 |

8 |

2,88 |

|

Finland |

23 |

8 |

2,88 |

|

Slovakia |

23 |

8 |

2,88 |

|

Azerbaijan |

20 |

7 |

2,86 |

|

Sweden |

26 |

10 |

2,60 |

|

Hungary |

26 |

10 |

2,60 |

|

San Marino** |

13 |

5 |

2,60 |

|

Kazakstan |

18 |

7 |

2,57 |

|

Bosnia-Herz. |

23 |

9 |

2,56 |

|

Georgia |

23 |

9 |

2,56 |

|

Montenegro |

13 |

6 |

2,17 |

|

Kosovo |

3 |

3 |

1,00 |

The diversity index works by dividing the accumulated number of UCL places over the years by the numbers of clubs taking part. Liechtenstein does not enter clubs into the UCL

Since the modern UCL began in 1994/95, the English Premier League has been awarded 90 places in the UCL and only 10 clubs have taken them up.

Four clubs from English football’s big six – Liverpool, Tottenham, Chelsea and Arsenal – made the finals of the UCL and the Europa League in 2018/19, and the last new club from England to qualify for the UCL was Leicester in 2016/17.

The same quartet of La Liga clubs as last season will take part in the 2019/20 UCL and another 24 countries will again be represented by the identical representatives as in 2018/19.

Domestic hegemony is evident in many leagues across Europe.

PFC Ludogrest Razgrad and TNS have won eight successive titles in Bulgaria and Wales respectively. The longest unbroken reign is in Belarus, where BATE Borisov have won 13 titles in a row.

Greece remains the least diverse country in the UCL. Over the last quarter of a century, only four clubs have taken the 50 places offered by UEFA to Greece, while just three Croatian sides have taken up 27 slots.

Despite an increasing amount of its members even at lower levels regularly reappearing in the UCL qualifiers each season, the European Clubs Association (ECA) wants to reform European club football.

This is widely viewed as attempts by some big clubs, such as Juventus, whose chairman Andreas Agnelli has the same role at the ECA, to create a form of European super league having monopolised their own domestic leagues.

Juventus finished 11 points clear of runners-up Napoli in 2018/19 to win their eighth successive title in Serie A, which is one of the most predictable competitions in Europe.

Most and least exiting leagues finishes

Ironically, the ECA meeting took place in Malta, where the local Premier League saw the most exciting finish of any league in Europe. Valletta only retained their title after finishing level on points in the league with Hibernians and winning a play-off on penalties after a 2-2 draw.

Apart from Malta, the next closest title race in Europe was in England. Manchester City finished just one point – or 0.9% of all available points – ahead of Liverpool to retain their title in the Premier League, which opposes reforming the UCL.

Bayern Munich won a seventh Bundesliga title in a row in 2018/19, but the race was close. Bayern’s winning margin was just 2% of all available points, making the German league amongst the 10 closest in Europe.

The most predictable competition was Israel’s Ligat Ha’al, where Maccabi Tel Aviv’s winning margin was 28.7% of all available points. France’s Ligue 1, which Paris Saint Germain has won every year since 2012/13 apart from 2016/17, was also amongst the most predictable. See full table.

Any reform of the UCL would be likely to further diminish the status of smaller more financially fragile European leagues, where even the scraps from UEFA’s top table can often buy dominance, simply to satisfy giants such as PSG and Juventus that play in predictable domestic competitions.

Editorial note: The article's Table 1 and the information on the last English club to qualify for the CL has been corrected in accordance with the well-spotted reader observations below.

"last new club from England to qualify for the UCL was Everton 14 seasons ago". What about Leicester in 2016/17?

Holland had 7 UCL-participants, not 6. PSV, Ajax, Feyenoord, AZ, FC Twente, SC Heerenveen and Willem II.