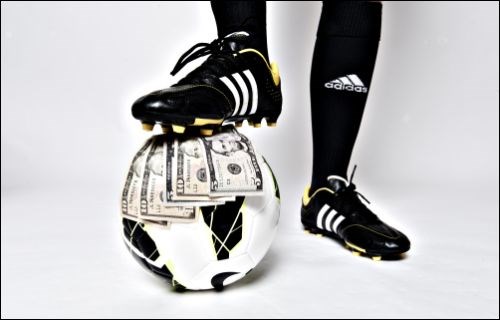

Is Financial Fair Play in European football any good?

It is a common characteristic of professional European football that it suffers from financial problems. Even the 'big five' leagues (England, Germany, France, Italy and Spain) face increasing debts and deficits. The clubs tend to overspend, and that has led UEFA to implement FFP, which aims at getting the clubs to live within their means.

Most recently, clubs like Manchester City and Paris Saint-Germain have been sanctioned for failing to meet the new regulations.

However, in the wake of the development and implementation of Financial Fair Play (FFP), several economists have criticised the regulation and questioned its potential.

Overall, there seems to exist three main strands of critique against the Financial Fair Play-program:

- FFP hinders necessary capital injections to financially distressed clubs

- FFP prevents competition in the player market and serves as a U.S. salary cap without improving competitive balance

- FFP ‘freezes’ the existing club hierarchy and makes it impossible for small clubs to break the existing hierarchy.

The Swiss economist Egon Franck, who has advised UEFA in forming the principles behind the Financial Fair Play, disagrees with all three strands and argues that, contrary to what the critics say, FFP will benefit European Football.

Does FFP hinder necessary capital injections to clubs?

The first point of critique of the FFP concerns the need for clubs to have money injected if they get into financial trouble. According to the critics, the clubs’ overspending is not a problem and the central rule that the clubs must break-even is therefore superfluous.

Critics say that intervention is unnecessary because clubs losing money is not a problem to outside society as long as creditors, rich owners or other stakeholders wish to spend their money supporting them.

According to Franck, the problem is, however, that clubs who continue to survive even serious economic problems start calculating with the fact that they can get away with spending more than their budgets allow. The European football clubs are in general too big to fail, which means that they expect to be bailed-out, should they fall short on capital.

This means that instead of taking hard managerial decisions regarding the football product, the clubs are busy pleasing sugar daddies and other club creditors.

Based on the soft budget constraints theory developed by the Hungarian economist Jànos Kornais, Franck argues that, in the long run, this will make the problems of European Football worse.

Just as the Hungarian economy suffered from scarcity behind the Iron Curtain, due to state intervention that balanced inefficient public enterprises’ deficits, the football product may suffer from a lack of innovation and effective management, since the clubs will never have a real incentive to function within their abilities and ensure happy football consumers. As long as European football functions under a soft budget constraint, dead serious considerations regarding profits are not properly taken into consideration.

The demand for players will continue to rise, creating a cycle of over-investment, because the clubs can expect to get help if they cannot pay the bill. Management and good governance concerning the important development and operation of the football clubs will be of less importance than the extravagant spending.

According to Franck, this will never be for the good of neither European football nor the clubs themselves.

Does FFP constrain a competition in the market for players?

The second strand of criticism is that the FFP constraints player salaries and is comparable to US major league salary-caps.

Assumed, as it is, salary-caps limits clubs' salary expenses and improves competitive balance. Combined with redistributive mechanisms in terms of spectator and television revenues, 'rookie drafts' etc. it creates a more even level of sporting competition between the U.S. teams.

In the open European leagues, however, such a tool would not affect the competitive balance, critics say - including the English sports economist Stefan Szymanski. In general, they believe that it is inappropriate to restrict the clubs' ability to invest (overspending and building debt) because this is the way business works.

In reply to this, Franck argues that it makes no sense to say that free and unlimited (over-)spending on players and player salaries creates a better situation than ensuring that clubs do not actually spend more than they have.

How can letting go of the problems of over-spending improve the current situation, asks Franck. Compared to the U.S. salary-caps, Franck sees the FFP rules as relatively soft, and even though the rules may not contribute to improved competitive balance, this was never the primary purpose of the program.

In a European context, Franck points to many other ways to ensure exciting matches, and the promotion and relegation system – which also ensures an opportunity to play other top teams via the European tournaments – is a way to maintain tension in the competitions. The clubs are continuously promoted and relegated based on their current level of competition.

If a club is relegated, its matches the following seasons will be more equal – and vice versa.

Does FFP ‘freeze’ the existing hierarchy between the clubs?

The last of the main strands of criticism is an argument that FFP will 'freeze' the existing hierarchy between the clubs because smaller clubs are unable to gamble to the same extent or invest at the same level as today’s big clubs have been capable to .

This puts the established clubs in a favorable position because they have already made the investments that the smaller clubs are now prevented from making. Some researchers have pointed out that this may even conflict with EU competition law.

This point is also rejected by Egon Franck. He says that the argument of a frozen hierarchy seems to rest on the assumption that the only way that smaller clubs can compete is by significantly overspending while hoping for an economic rescue.

In his opinion, this is not only an untenable situation at the outset, but the argument does not stand because according to Franck, FFP only limits ‘inflated’ contracts, meaning what can be defined as ‘over-price’-deals with willing owners or patrons.

In theory, there is no maximum to the amount of money poured into the clubs as long as it reflects a fair market value transaction between a club and an extern party. The only difference is that the deal must be completed in a regular manner and not work as a financial rescue. According to Franck, this restriction will have favorable effects on incentive structures as well as club management.

The end of the 'zombie race'

Generally, Egon Franck rejects that smaller clubs should have better chances of competing if FFP was abandoned.

According to the Swiss professor, sugar daddies will (continue to) seek towards clubs that are already big, because these clubs – ceteris paribus – have a better chance of maintaining or expanding their success. If FFP does not regulate capital injections, this becomes a self-reinforcing effect, where the big get bigger. In other words, the exact opposite effect than what critics argue that FFP will entail.

FFP will essentially force clubs to focus more on better management rather than merely following the logic of the big wallets. It will change the 'zombie race', that the sporting arms race between the clubs has turned into: Technically insolvent clubs that infect each other with poor financial management because everyone is trying to keep up with the upward wage spiral, while hoping for bailout by public or private actors when unsuccessful.

Contrary to what critics suggest, a positive side effect of FFP is financially healthy clubs that are run within their means, and on the basis of their real self-created market potential, says Franck.

This will not only create a better industry, but may even strengthen the competition on the market, instead of the current situation where the deepest pockets decide the game.

More information

'Financial Fair Play in European Club Football - What is it all about?'

UZH Business Working Paper Series. Working Paper No. 328, April 2014. University of Zurich.