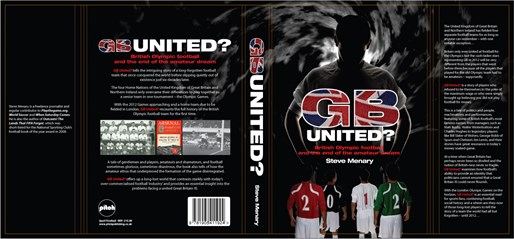

GB United? British Olympic Football and the end of the Amateur Dream.

This is the first chapter of the bookGB United? British Olympic Football and the end of the Amateur Dream by author and journalist Steve Menary.

Introduction

“It would be great if our country could have a football team in the Olympics. To perform at the Olympics would be special for a lot of players. I might come out of retirement – if I’m retired by then!”

David Beckham, 2005

On 6 July 2005, Britain was alive with news that the world’s biggest sporting event was coming. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) had decided that in 2012, the Olympic Games would return to London, bringing the best athletes from virtually every sport on the planet, including one that few in Britain associate with the modern Olympiad – football.

Of all the Olympic sports, football today seems most out of kilter with the original Olympic spirit. A game obsessed with money. Wages, debts, transfer fees all seemingly inflated beyond belief. But football was not always like that. Just like the Olympics, football’s origins lay in playing the game for sport, for fun. Most people still play football that way today; the tackling rougher, the passes less accurate, but for no reward other than simply playing the game of football.

Britain’s last involvement with Olympic football had petered out more than three decades before London won the rights to host the 2012 Games and the prospect of a home team drew great interest.

“It would be great if our country could have a football team in the Olympics,” said England star David Beckham after London won the bid in 2005. “To perform at the Olympics would be special for a lot of players. I might come out of retirement – if I’m retired by then!”

But not long after those initial heady days, the squabbling over international football’s greatest anomaly began. In the Olympics, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is represented by one team in all sports. In football, the independence of the four Home Nations dates back to the game’s origins. No one was giving up their autonomy.

“The FAW will not undertake anything that would jeopardise its position as a separate nation within Fifa and Uefa,” said Football Association of Wales (FAW) secretary general David Collins. “Wales doesn’t want to compromise its position as a separate nation within Fifa and Uefa. It wants to continue playing football internationally as Wales. And I must say that everything I’ve heard from the Welsh media and the supporters in Wales fully endorses the [FAW] council’s decision.”

Fifa’s statutes included a special, longstanding rule permitting the independence of the four Home Nations. In 2004, these statutes were revised as part of a centenary project. Fifa’s executive committee discussed the “British statute” but its continuing role was not even put to a vote. Any of Fifa’s 208 members can question the statute. A change would require support from three-quarters of Fifa’s members but no challenges ever emerged because for many years there was little justification. London 2012 changed all that.

By late 2005, the Scotland Football Association (SFA) and the FAW had insisted that unless Fifa president Sepp Blatter back up in writing his verbal assurances that taking part in the Olympics would not damage their independence, they would not take part in 2012. With the Irish Football Association (IFA) representing Northern Ireland sitting warily on the fence, but then Prime Minister Gordon Brown advocating a united team – and Sir Alex Ferguson as manager – England’s Football Association (FA) were in a politically impossible position.

When David Will, a Scottish lawyer and former Fifa vice president, warned in October 2007 that Blatter’s verbal assurances could not be relied on, a united team was all but finished. Will told the BBC:

“There’s nothing to stop an association saying ‘the four British associations have played together at an Olympics so they can do at a World Cup as well’. We should not take the chance of joining a British team. I’m sure Sepp Blatter means what he says but why should the associations take that chance? I have never accepted that we should take such a risk. It is more important to be in the World Cup as independent associations than in the Olympics as one. For many years there were threats to the independence [of the Home Nations] and those could surface again.”

Blatter subsequently shifted his position in March 2008. To end British bickering over the issue, he suggested that a team comprised solely of English players play in London.

In early 2009, the Northern Irish, Scots and Welsh wrote a joint letter to the FA opposing the whole concept of a GB Olympic XI and refusing to discuss the idea ever again. Secretly, however, all four associations were thrashing out a deal. The Irish, Scots and Welsh agreed to let the FA take sole charge and only Englishmen would be British Olympic footballers in 2012.

The pact took the international game in Britain back more than a century, when football and the Olympics combined to produce the sport’s first real world championship. Then, only Englishmen represented Great Britain too – and everyone played for free.

Few players desire international football for the money but appearance fees are paid, although not disclosed by the likes of the FA. In the Olympics, commercial opportunities abound and few athletes in any discipline could be described as true amateurs, but no one gets appearance money.

That ethos was the one so loved by the public schools and their alumni that developed and codified football. These were gentlemen bred to uphold the British Empire and often lead battles. A Corinthian ideal on how to play the game emerged long before Baron Pierre de Coubertin began to put his dream of reviving the Olympics into play. In the British Isles, solidarity was praised with matches played to the highest standards of sportsmanship.

Should an opponent lose a player to injury, good form insisted that the other side simply take a man off to even up the sides. Matches were not to be played for trophies and leagues were not tolerated.

A Victorian trend for codification saw rules of the game formalised in 1863 and the FA was formed in London to agree regulations. The FA’s founders, those who set themselves up to run the game, came from southern England, the universities and the public schools. The FA’s first meeting in the evening of 26 October 1863 at the Freemason’s Tavern on Lincoln’s Inn Fields in central London included representatives from prestigious public schools like Blackheath Proprietary, Charterhouse and Kensington.

Those few clubs present, like Crusaders or the No Names XI, were all southern. Their organisation was not the English FA but the FA, still to this day the only one set up with no geographical boundaries. The game was more developed in Britain than anywhere else in the world and England’s pioneers were all amateurs, gentlemen of the sport, purists. Men who believed in that Olympian ideal of sport for sport’s sake and neither wanted nor needed money to compete.

“You see, it is not worth the while of a university or public school man to run the risk of accepting payment for his services on the football field,” said Charles Wreford-Brown, England’s captain in the mid-1890s. “Taking wages and presents, a good pro makes about £5 a week all the year round but just think what a public school or university man, or anybody of social position, would lose if he were discovered taking money secretly.”

Born in Bristol in 1866, Charles Wreford-Brown is the epitome of the footballing gentleman. A fine all-round sportsman, who later played county cricket for Gloucestershire and chess for Britain, his football career started out in goal before the burly Wreford-Brown moved to centre-half. His skills won him five full England caps and his wit a footnote in the game’s history.

After leaving Charterhouse, Wreford-Brown went to Oriel College, Oxford. On leaving his digs one day with his sports kit a passing friend stopped Wreford-Brown. Public schoolboys of the day often added “er” to the end of words. Wreford-Brown was asked if he was playing “rugger” as rugby union was then known. Football was “association” or “soc” and, with a touch of wit, Wreford-Brown added the obligatory “er” and replied that “no,” he was off to play “soccer”. Football suddenly had a new name. It stuck.

Wreford-Brown loved football and the Corinthian spirit mirrored in de Coubertin’s new Olympic movement. Over the years, Wreford-Brown would lead efforts to keep these values untainted, reacting against increasing commercialisation that would prompt many of his peers to turn their backs on soccer.

When the FA Cup had been set up in 1871, the competition was dominated by Wreford-Brown’s social elite and their Old Boys’ clubs. Winners in the first decade included grand old names such as Old Etonians and Old Carthusians, a club for ex-Charterhouse students such as Wreford-Brown.

Football was also well established in Scotland, driven partly by the foundation in 1867 of gentlemen’s side Queen’s Park in Glasgow. Internationals between England and Scotland began in 1872. The Scottish FA (SFA) was created the following year – the first of many dividing lines in the history of British football.

The game changed rapidly as more people began to benefit from stopping work halfway through a Saturday. Working men now had time to play and watch this sport that the gentlemen loved. When organised football under the auspices of the FA had begun, all players were amateurs but secret payments quickly started.

By the 1870s, football was a popular spectator sport and clubs such as Aston Villa began taking gate money. Players in turn asked for travel expenses. The sport was drifting towards professionalism in both England and Scotland, where young Scotsmen were being lured south by better pay. The SFA responded by barring these exiles from their national team.

In 1882 the English FA ruled that a player receiving “remuneration or consideration of any sort above his actual expenses and any wages actually lost” would be banned for an indefinite period. Clubs immediately looked for ways round this rule. Ruses ranged from duplicate sets of accounts to paying players for non-existent jobs outside football.

To many of the gentlemen, money was perverting their sporting idyll. Nothing symbolised this ague more than Scotland routinely gaining the upper hand over England in the annual fixture. For ferocious English gentlemen such as NL “Pa” Jackson, this was simply untenable. A response was needed to combat money and the Scots. The answer was the formation of a private members’ club for university graduates and ex-public schoolboys to play together regularly and strengthen the England side.

Corinthian FC was created in the 1882/83 season to play friendly matches against the public schools and top professional sides. The aim of these matches was to instruct the opponents in how to play the game and also boost England. Over the next seven seasons, 88 England caps were awarded for the matches against Scotland – 52 went to Corinthian players.

The gentlemen had briefly re-established themselves but nothing could stop the juggernaut of professionalism. Underhand payments were rife. On 20 July 1885, the FA accepted that the situation was uncontrollable. Professionalism was ushered in.

Earnings varied from 30 shillings a week at Sunderland to players taking a cut of the gate receipts at Birmingham. To uncompromising Corinthian idealists like Jackson, these professionals were known as players. Anyone who played for free was a gentleman. In match programmes, professionals were listed solely by their surnames but amateurs’ initials were included as a prefix, so everyone knew who took money and who did not.

Jackson even preferred to separate gentlemen from players wherever possible outside of matches. When England sent a squad on tour to Germany in 1909, Jackson was reported as being “astounded” that amateurs and professionals in the team not only travelled in the same train carriages but ate and went to concerts together.

Not everyone was as obdurate as Jackson. Steve Bloomer, a leading professional with Derby County, recalled playing an international match against Scotland, when Wreford-Brown was his captain. The moustachioed Wreford-Brown played in long shorts with side pockets full of money. After each professional scored a goal, the patrician Wreford-Brown pressed a coin into the palm of the scorer’s hand.

The social divides were not as extreme as cricket, where gentlemen would often insist on separate dressing rooms from the professional players, but as football clubs in the Midlands and the North embraced professionalism and recruited working-class players, the isolation of the southern gentlemen amateurs increased.

The people that created the distinction between “association football” and “rugby football” and set down the rules were losing their grip, but chances to retain their status were there. When the Football League was set up in 1888, one early plan included seven professional clubs from the Midlands and the North and one from the South – the gentlemen amateurs of Old Carthusians – but to the league’s founders, like the Birmingham shopkeeper William McGregor, there was no place in his competition for these dinosaurs. Football’s history played out very differently.

The idea of an amateur club playing in the English professional league would linger for decades but the days of gentlemen winning the FA Cup were gone. In 1894, to sate the demands of ambitious gentlemen who wanted a competition that they could win, the FA set up the Amateur Cup. PA Jackson was chairman of the FA Amateur Cup Sub-Committee, who spent £30 on a splendid trophy. To put that sum in context, a farm labourer could expect £25 for a year’s work tilling fields.

That first tournament featured a host of clubs well established in the professional elite today, including Tottenham Hotspur, Middlesbrough, Ipswich Town and Reading. The first champions in 1894, however, were Old Carthusians, with Wreford-Brown dominant at centre-half. He missed the next year’s final, when Old Carthusians lost to Middlesbrough but returned in 1887 to claim another winners’ medal.

Corinthians sat out the competition, thinking it beneath them, but the Casuals, another amateur club set up for Old Boys from Charterhouse, Eton and Westminster, soon took part. The two clubs were always close (and shortly before World War Two would merge) and an early pact saw Corinth – as Corinthians were often known – standing aside to allow Casuals a clear run at the Amateur Cup, but the Old Boys’ clubs soon lost interest in the trophy. Old Carthusians did not even bother to defend the trophy they had won in 1897.

Many of these gentlemen’s clubs existed in a sporting nether world, oblivious to changes in the sport, notably the introduction of the penalty kick in 1891, which was deemed unsporting and often simply ignored. “Penalties are an unpleasant indication that our conduct and honesty is not all it should be,” an Old Carthusians official told The Times after a debate between the club and Casuals before the 1894 Amateur Cup final in Richmond.

When the Arthur Dunn Cup for public schools later began in 1902/03, many of the Old Boys’ clubs quit the Amateur Cup for their own exclusive competition, away from the established amateur game, now often full of working-class amateur teams. Seeing their peers sidelined on the pitch, gentlemen like Pa Jackson and Wreford-Brown, who loathed gambling on sport, saw money streaming through the game and instead looked to influence the running of the game.

In 1886, the FA introduced match fees for internationals of 10 shillings a game. Amateurs playing for England took nothing. In 1891, the Football League first tried to regulate wages. This was partly to pacify the avarice of club owners but also underpinned the amateur game by making professionalism unpopular in terms of earnings for any gentlemen tempted to go pro. Initially, players could earn no more than £10 a week. This was a maximum not an average, and for the next 70 years footballers would struggle to free themselves from this yoke.

In 1901, the clubs tightened their grip. A maximum wage of £4 a week was put in place. That wage was twice what a works foreman earned and four times a farm labourer’s take-home pay. Only the very top players received such a sum, while a works foreman and farm labourer generally had better terms and conditions than a footballer. The game also developed the invidious retain-and-transfer system, where players were kept at clubs after their contract expired. Unless transferred or agreeing to a new club proposed contract, players had to stay with the club – usually unpaid.

A fledgling players’ union foundered in 1901 but six years later the Association of Football Players and Trainers Union (the forerunner of the PFA) was formed. Negotiations with the Football League produced a rise in 1910, taking the maximum wage to £5 – on the proviso this was paid in two rises of 10 shillings apiece after two and four years of service respectively.

When World War One broke out, wages were cut until after the war. The union protested and a rise to £9 a week was secured in 1920. International match fees, last increased in 1908 to £4 a game, went up to £6 a game. For non-international players, this settlement was not great. Players new to the league started on £5 a week and the new rise came in increments of an extra £1 per week each year. To reach the top of the pay scale was a lengthy business. The union protested, asking for £10 a week, but membership was weak.

In 1922, the league draconically cut the maximum wage to £8 in the playing season and £6 in the 15-week summer break. The PFA agitated but the limit stayed right up until 1945, when the close-season rate went up to £7 a week. By comparison, average manual workers then were earning about £24 a week. Little wonder that playing football was seen as unattractive.

A handful of talented amateurs with sufficient time to train played in the Football League but with many eschewing the professional game altogether, a flourishing amateur scene developed around northern England and the London area. Gentlemen such as Wreford-Brown had mostly vanished from the pitch but their influence within the FA produced legislation to protect their credo.

An amateur who tried but failed to break into the professional game faced an uncertain future. Players needed to seek reinstatement as an amateur from the FA. This was possible but far from certain. Former Olympian Hugh Lindsay, widely regarded as one of the most talented amateurs never to turn professional, explains that:

“If you didn’t make it as a pro you couldn’t even play on a Sunday. All you could do was go into the Southern league with the other old pros. In some ways, the professional game was a bit of a closed shop, them and us between the amateurs and the professionals. If you went in as a mature person, you were looked on as an amateur because most of the lads had been apprentices and cleaned the boots. If you waltzed in at 20 or 21, you weren’t always looked on that favourably.”

The maximum wage continued to make the professional game unattractive for anyone with aspirations of a decent wage but in 1947 the PFA achieved its biggest breakthrough by forcing the introduction of minimum pay levels. At the bottom, a professional aged between 17 and 18 would be paid at least £3 a week. For players aged 20 and over, the base rate was £7 a week in the season and £5 in the break. These negotiations, which involved a National Arbitration Tribunal, set the maximum wage at £12 a week in the season and £10 a week in the summer. This ruling applied to England, Scotland, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

Another raise was secured in 1951 – to £14 a week – and the next year, playing internationals became even more attractive when appearance fees surged 50 per cent to £30 a game. As the austerity of the 1950s passed, earnings were gradually pushed up to a playing season maximum of £20 with a floor for players aged over 20 of £8 a week. Most players outside the top flight, however, still earned less than the maximum set by the Football League right back in 1891, but the restrictions put on the game were slowly unravelling.

Entertainment tax had been introduced during World War One, but in 1957 activities such as football and theatre were exempted. This freed up more money and the players knew it. In 1960, when the average manual worker’s wage was £56 a week, Jimmy Hill’s PFA made further wage demands that were backed up by a strike threat. The following year the league caved in. The maximum wage was finally abolished.

Football became even more of a free-for-all as amateur clubs used money from the entertainment tax exemption to fuel higher secret payments to players. This had always gone on but shamateurism as the practice became known was rampant by the 1960s. The FA again tried to legislate with rules, such as banning players from signing for clubs more than 50 miles from home. This was aimed at stopping teams that flagrantly attracted the best players with big enough secret payments to make lengthy trips worthwhile, but the amateur ideal was in its dog days; nowhere more so than at the Olympics.

The amateur code had supported British footballing efforts at the Olympics, which ranged over six decades from glorious success to failures that were sometimes pitiful, sometimes valiant. For the amateur players, the Olympics was the peak of their ambition, offering an often once-in-a-lifetime experience rarely available to their peers, an opportunity to mix with the world’s greatest athletes in all disciplines, a chance to travel to places that so many people could only dream of. This is their story.

Steve Menary is a regular contributor to Play the Game and his new book on the history of the GB Olympic football team, ‘GB United? British Olympic football and the end of the amateur dream’ is published by Pitch Publications.

The book can be ordered at https://www.amazon.co.uk/GB-United-British-Olympic-Football/dp/1905411928/ref=sr_1_4?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1283774855&sr=1-4

-

David Ballheimer,

25.02.2011 10:55:

This looks a very intriguing book. What is the chapter breakdown, i.e. how much space is alloctated to each GB team between 1908 and 1972, the last time the team was eligible to compete? I am particularly interested in the 1948 team, coached by Matt Busby.