Sport Financing: European Model Facing a Risky Future?

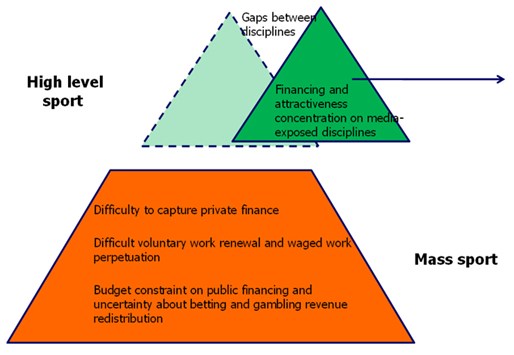

The European model of sport is built up along a so-called pyramidal structure based on mass sport operating thanks to significant voluntary work; top of the pyramid is made up of high level – including professional – sport. A mutual solidarity tightly links the top to the base.

The study on sport financing achieved in the framework of the French presidency of European Union (EU)1 has come to the conclusion that the aforementioned model nowadays encompasses some dimensions which are increasingly fragile.

A financing orientation detrimental to mass sport

Private finance flows into sport from households’ and enterprises’ expenditures. The latter basically come from sponsorship and television (TV) broadcasting rights, and are primarily geared towards high level sport. According to available data, 90% of TV rights and sponsorship expenditures are devoted to high level sport while only 10% remain for mass sport. The media factor deepens the financing gap between sporting disciplines.

State (governmental) financing is also leaned to adopt the same criteria of sporting performances and media exposure so that nearly 60% of state finance2 dedicate to either specific high level sport practices or sporting federations’ budgets. In both cases, money is targeted to the highest level performances and big international sport events. Such a result exhibits some ambiguity about governments’ priorities: governmental policies strongly publicize health and social outcome of sporting activities whereas finance concentrates on high level sport.

Mass sport practice basically relies on voluntary work, and on money brought by local authorities and sport participants themselves. Though providing twice as much as the state budget to sport finances, local authorities are left (except in a few EU countries) with a less structuring action in sport due to their scattered and fragmented financial contribution. The role of local authorities is rather limited with regard to sport governance and confined to coordinating various financing sources and their impact on the development of local sport participation.

Solidarity mechanisms based on revenue and finance redistribution are widespread in 21 out of 27 EU countries whether being vertical solidarity between media-exposed and mass sports or horizontal solidarity between different sport disciplines, or even both (like in France with a tax on professional football redistributed toward all other sports). However, money amounts involved in such redistribution are not enough to fill existing gaps between ‘rich’ and ‘poor’ sports. The top and base of sport pyramid tend to dissociate from each other.

A same empirical and political tendency has already been observed by various bodies such as the International Association for Sport and Culture and it is confirmed in our analysis of sport financing structure.

Other risk factors hanging over sport financing

Two other risk factors are of a threat to the European pyramidal sport structure. Voluntary work is hardly renewed at the same pace as before although it is a first order human resource for mass sport functioning and a foundation of what makes the European model of sport so specific. On the other hand, public monopolies over sport betting and gambling will soon have to comply with European competition (anti-trust) policy. The share of these monopolies’ income which was redistributed to sport in 2005 represented about 30% of public sport financing in Europe. Governments’ sport policies are at bay now with competition policy compliance.

How make safer a more stable sport financing in Europe?

The most powerful lever to stabilize safer sport finance would consist in channeling more household finance into mass sport and sporting associations. As a counterpart for more household money, sporting organizations have to refurbish and renew their supply of sporting activities and services, and upgrade their quality standards in order to attract a bigger share of overall population into active sport participation. However state regulation policies could also help, for instance in reorienting a share of VAT (value added tax) revenues levied on sport goods and services – including VAT on sport media – toward sport organizations.

Such measure, which is not in tune with current fiscal policies in European states, could be temporary, namely covering the span of time during which financial and economic crisis will spread. It would aim at energizing the sport sector with hiring more waged workers, boosting voluntary work, renovating sport equipments and infrastructures and so on, and developing customer loyalty to sport on the demand side. Some tax incentives focused at individuals and enterprises that invest in sporting activities with public utility recognition would also be likely to trigger more support from private financing to sport organizations.

A second lever pertains to (vertical and horizontal) solidarity mechanisms within the sport sector itself, since they are among the most original components of the European sport model and clearly delineate the sport industry specificity compared to all other industries. In past recent years, a swift increase in financing of elite sport has been witnessed and has put solidarity mechanisms under a strong pressure.

It would be worth institutionalizing and more precisely formalizing such mechanisms in order to guarantee their durable operation in the future. In addition, creating some substitutive tool to redistribution of betting and gambling revenues for sport is required. This could proceed with a special tax exemption on sport activities.

A third lever is related to overall sport governance and connected with the distortion between economic significance of local authorities in sport and their weak participation to sport committed nation-wide decision making. Local authorities would probably be called for a better coordination – namely between different hierarchical authorities over municipalities, counties, regions, and between border localities and provinces – of their sport financing and interfering in nation-wide sport policies.

These few examples show that sport public policies can adopt levers and tools that make sport financing safer together with strengthening the autonomy of sport sector.

| A few markers The amount of sport financing per inhabitant goes from 8 euros up to 500 euros in different EU countries, in 2005. The ratio of overall sport financing to GDP is varying between 0.20 and 1.76%: it is an increasing function of GDP per capita level. A 24% growth has affected this ratio in 2005 compared with 1990. The estimation of overall sport financing for the whole EU27 countires isin the range of 160 to 170 billion euros (i.e. 340 euros per inhabitant on average, and nearly 1,5% of European GDP) |

1) Amnyos, Etude du financement public et privé du sport (Study of public and private sport financing), French State Secretary for Sports, Paris, October 2008.

2) The above mentioned study takes into account only current state budget expenditures, excluding capital expenditures.

A more elaborated version of this study can be found in our Knowledge Bank. Click here to read the Knowledge Bank article.