"Now that it's fall and the blind will be leading the blind until mid-June, there is a new assortment of cheerleading hockey books out there. Playing With Fire is the antithesis," Laura Robinson writes in her review of hockey player Theo Fleury's new book.

Theo Fleury—all 5’6” of him--is in my living room. He’s sprawled on the couch, cowboy boots on the coffee table, coffee cup (not beer bottle) in hand, wearing a Hugo Boss outfit from his NHL days telling me, via the pages of his book, another tale from “The Show.” This one from his 1988-89 Calgary Flames Stanley Cup win.

“I had experienced a major win at the World Juniors, so I knew what the process was. ‘Don’t get too excited, just stay calm. You can’t start thinking instead of reacting.’ My play had to stay instinctive. As I skated out on the ice that night I just wanted to shit with excitement. I was thinking, ‘Where the hell are my dad and mom sitting? They must be going bonzo.’ Fleury’s are French—emotional, crazy. I felt an exhilarating anticipation, mixed with anxiety—‘Fuck, can we just win this and get it over with?’”

A typical sprinkle of expletives in the above paragraph, but not a typical story—because of the happy ending (though Fleury was “hammered” before he left the dressing room that night, and continued drinking with the team on their flight home and became “annihilated”).

Now that its fall and the blind will be leading the blind until mid-June, there is a new assortment of cheerleading hockey books out there. Playing With Fire is the antithesis. Start with the sadness and hunger of a little boy who comes from small town prairie poverty that chills even in August; an embarrassing and disgusting alcoholic father, and a prescription pill-popping, religious zealot mother, it hard to believe Fleury survived his own life. He certainly tried to accidentally take it enough times by driving drunk, stoned, depressed and paranoid while raging with anger.

As he spun in yet another downward spiral in 2001 he figured, “…I couldn’t have a relationship with myself. The funny thing is, the higher I rose in society, the more alone I became. Why? Because I was treated differently and dehumanized. I knew that half the time people were nice to me because I had money or I was a hockey star.”

Neither parent was there for him in childhood; luckily the good people who ran minor hockey in Russell, Manitoba gave him community and love, but he didn’t have a chance as soon as coach and sexual predator Graham James spied him at the Andy Murray hockey camp in Brandon, Manitoba when he was scrawny and thirteen. James could spot a troubled kid a mile away, and though Fleury doesn’t name names, he and Sheldon Kennedy were far from his only victims. This story of abuse will blister and boil for generations as abuse begets abusers, but thanks to these brave men, an environment where “telling” and healing is a little easier has been created.

As Fleury outlines time and time again, the WHL, NHL and Hockey Canada viewed him only as meat. He gave plenty of “dirty” drug tests, substituting Gatorade or his kid’s urine, but their solution was to help hide his addictions. Even the substance abuse program they put him on, he says, was about getting him back on the ice so seats were filled and money made, not addressing childhood neglect and sexual abuse. It was also about hiding hockey’s dirty little secret: He wasn’t the only NHL gambling alcoholic who hit strip bars looking for sex and cocaine every night.

When, in 2003 he backed out of his contract with the Chicago Blackhawks, Fleury figured, “…the whole league reacted to my leaving the way you would feel after having a big, happy dump. There were a lot of guys like me in the game, but they didn’t want anyone to know that. My presence kept the bad news on the front of the sports pages. Hockey wants to be known as the school’s good-looking, clean-cut jock, and I was really fucking with that image.”

I loved opening the book only to have Fleury wrestle out and talk to me for another couple of crazy energy hours. How smart it was to keep the angry and often funny vernacular of the locker room. If I tell you how he starts to heal, I will give too much away, but it sure helped that instead of prescribing more drugs, as all the other doctors seemed to, Robin Reesal and Joanna Mogab got him talking about sadness. I will, however, repeat the last words because they matter so much.

“So if you are a kid who is in the situation I was in, and somebody older is using you for sex, call for help. You can call the police or you can search for kids’ help lines on the Internet. Seriously, you are not alone. Pick up the phone.”

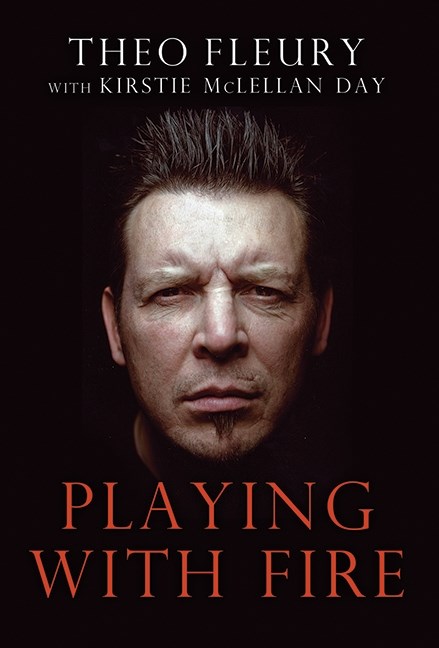

Title: Playing with Fire

Authors: Theo Fleury, Kirstie McLellan Day

Publisher: Harper-Collins

ISBN: 978-I-55468-239-3

322 pgs

Laura Robinson wrote “Crossing the Line: Violence and Sexual Assault in Canada’s National Sport.” Her children’s book, “Cyclist BikeList: The Book for Every Rider” will be published this spring. She coaches the Anishinaabe Racers mt bike and Nordic ski team at Cape Croker First Nation Elementary School.

This book review first appeared in the Globe and Mail and is reprinted at playthegame.org with kind permission of the author.

Laura Robinson wrote “Crossing the Line: Violence and Sexual Assault in Canada’s National Sport.” Her children’s book, “Cyclist BikeList: The Book for Every Rider” will be published this spring. She coaches the Anishinaabe Racers mt bike and Nordic ski team at Cape Croker First Nation Elementary School.

This book review first appeared in the Globe and Mail and is reprinted at playthegame.org with kind permission of the author.