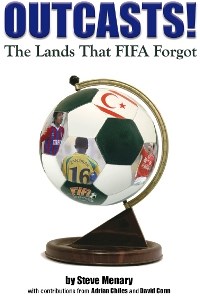

Outcasts! The Lands That FIFA Forgot

19.09.2007

By Steve MenaryThis is an edited extract of "Outcasts: The Lands That FIFA Forgot", which is published by Know The Score books on September 27. ISBN-10: 1905449313. ISBN-13: 978-1905449316.

More details at outcasts-book.blogspot.com

"Outcasts! The Lands That FIFA Forgot" examines the much tarnished reputation of FIFA, the governing body of world football, and just how they justify the exclusion of some 'nations' from their organisation while welcoming others. For two years, I traced the incredible journeys of the teams that FIFA refuse to recognise - either for reasons of political expediency, or because FIFA just believed they could not compete with the likes of Montserrat on the world stage.

23 February 2006, Monaco Consulate, London

A crowd of around two dozen Turkish Cypriots gather in freezing weather outside Monaco’s consulate at Cromwell Place in south Kensington. A slightly bemused male member of the Monegasque consulate emerges and politely takes a football covered in graffiti and letters of protest from the leader of the protestors, Ipek Ozerim. The Turkish Cypriots carry banners with ‘Monaco: play fair’ and ‘Keep politics out of sport’ and brandish red cards with ‘Non’ printed on them. A song strikes up, twisting a well-known terrace chant into North Cyprus, we’re by far the greatest team the world has never seen” to the bemusement of passers-by.

The independent Republic of Cyprus was formed in 1960 after a long battle for independence from Britain led by the EOKA activists. A treaty of establishment created what most people know as Cyprus, but the Turks and Greeks who inhabited the island were not split up in that grand colonial tradition of arbitrarily drawn lines.

A year later, the KTFF claimed former FIFA general secretary Dr Helmut Kaser agreed that the Turkish Cypriots could play friendlies against FIFA members, but not official competitions. Ad-hoc ‘internationals’ were played by Northern Cyprus against Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Libya and Malaysia but this ended in 1983. That year, attempts at resolving the conflict were sent spiralling into retreat, when the Turkish-zone declared itself as the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) led by nationalist president Rauf Denktas.

When Cyprus was granted independence, the Turkish Cypriots insist this enshrined the right for separate sporting institutions, but only the Republic Cyprus, the Greek partition, is recognized by UEFA and FIFA. In 1996, the KTFF applied to join FIFA, but were rejected. Players from Northern Cyprus are not helped by rules in the Turkish football league. As the TRNC is a separate state according to the Turkish government, players from Northern Cyprus are treated as overseas players. For ambitious players from TRNC that want to play a higher standard of football, the obvious place to go – Turkey – is one of the hardest to break into. Mete Adanir played in the Turkish top flight a decade ago only to die in a car accident. Kenan Özer is at Besiktas but only plays sporadically. The most famous Northern Cypriot players today are actually two that played in the Greek Cypriot league.

Sabri Selden left the TRNC in 2002 to play football for Nea Salamina and found himself branded a “weak character” by North Cyprus president Rauf Denktas, as departure was seen as a public relations coup for the Greek Cypriots. His brother Raif later followed Sabri across the border to play football.

The departure of the brothers was a cause célèbre, but as relations eased slightly between the two sides, a move by another Turkish Cypriot player to the Greek Cypriot league proved less controversial. In April 2005, Denktas was ousted in elections and replaced by the more moderate and younger Mehmet Ali Talat. Relations eased between the two sides and crossings through a border hidden away in Greek Nicosia became a daily occurrence. Around 4,000 Turkish Cypriots cross daily to work in Greek Cyprus, where per capita income is estimated at ten times higher than in the North.

Like Selden, Coskun Ulusoy just wanted to play a higher standard of football. He studied in Istanbul between 1994 and 1999, but could not find a professional club because of the rules treating him as an overseas player.

“Everyone asks me what is your nationality and I say ‘Turkish part of Cyprus' and everyone has the same answer: ‘that is a problem’,” explains Ulusoy. In Northern Cyprus, he played for Girne – or Kyrenia as the Greeks know the pretty harbour town – but in 2004 was offered a £9,000-a-year contract with Nea Salamina, which has a left-wing fan-base. Every day, he traveled back and forth across the border to training. Though he received some abuse, Ulusoy only has good memories of his two years with Nea Salamina. He returned to the TRNC after his mother-in-law was not well and took a job at the interior ministry. Ulusoy adds: “When I cancel the contract, they [Nea Salamina] are very sorry. I never forget they said to me they lose a friend and I said that I lose many more friends.”

Ulusoy’s move to the south came during a time of big change in the isolated territory’s status in political and football terms. Talat took over as President, but a two-year series of talks between the leaders of the two communities brokered by the United Nations failed to reach an agreement to reunite the divided island. The Turkish Cypriots had supported the EU plan, but it was rejected by the Greek Cypriots in an April 2004 referendum. The following month the entire island of Cyprus joined the European Union. This entry only applies to the areas under direct government control and not parts of the TRNC, but Turkish Cypriots are eligible for Republic of Cyprus citizenship and can enjoy the same rights as other EU citizens. What the Northern Cypriots want is a system modeled on the UK in political and sporting terms. Not too much to ask?

Since the EU admission, border crossings have become routine. Not only were Turkish Cypriots such as Ulusoy crossing regularly, but so were Greek Cypriots back to the north, where the only industry is tourism, subsistence farming and a construction boom providing hotels and holiday homes. Those holiday homes are increasingly being bought by British holiday makers – the only problem is that some of these homes have been built on land seized from Greek Cypriots, who remain their legal owners in the eyes of the EU.

Some Greek Cypriot restrictions remain in place, but appear more to do with mainland Turkey than their fellow Cypriots at the top end of their island.

In July 2005, Reporters Without Borders, a lobby group that defends press freedom, slammed the Republic of Cyprus for refusing to allow Turkish journalists based in the TRNC to enter the country to cover a competitive football match between Greek Cypriot side Anorthosis Famagusta and Turkish side Trabzonspor. According to Reporters Without Borders, Turkish nationals wanting to travel to Greek Cyprus for professional reasons need to seek permission two days in advance. Reporters from the TRNC are not subject to the same restrictions and were allowed to cross the border by the Greek Cypriot police. But any Turkish journalists that tried to get into the game on 25 July were refused entry. This time, the Northern Cypriots were not the ones being isolated but their sponsors.

The game was to be a great night for Cypriot football and the closest a team from Cyprus had got to the Champions League. Having eliminated Dinamo Minsk of Belarus in the first qualifying round, Anorthosis Famagusta routed Trabzonspor 3-1 and went through 3-2 on aggregate to the third and final qualifying round, where they lost to Glasgow Rangers.

The problem for many visitors to Northern Cyprus is that the place appears rather like an outpost of Turkey itself. Even the flag is merely the Turkish standard with the colours reversed, as is the spend Turkish lira, Cypriot pounds, Euros, even English pounds, but there is no Northern Cypriot denomination. There is investment, but due to the lack of recognition this is mainly from Turkey, although also occasionally by the Israelis. The post boxes are still the blue ones put in decades ago by the British colonial authorities, but all post has to go via mainland Turkey.

To the Greek Cypriots, Northern Cyprus remains a part of their country that has merely been sectioned off and their people driven out after the war. Despite the EU negotiations, the TRNC is at the heart of the stalled EU application by Turkey, which insists on recognition for Northern Cyprus and the establishing of direct trade and economic links to support reunification. The Republic of Cyprus are not having any of this and are blocking any attempts that would lead to the TRNC being recognized as a country in its own right in any way.

These frustrations lead to the TRNC to try and secure a different form of national recognition – on the football field. The KTFF and the TRNC government decided that rather than wait, an international side would be launched at the 250,000-odd residents of Northern Cyprus, who were more used to watching the likes of Galatasaray on television in the Champions League than their own home-grown players.

In the summer of 2004, the KTFF assembled a side that was taken to Norway to play the Sápmi team representing ethnic Laplanders. That was followed up by a tournament hosted in Northern Cyprus to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the KTFF. The Sápmi were invited for a re-match. Kosovo, a UN protectorate and still part of Serbia to the Serbs and Russia, also took up an invite. Monaco were also invited, but could not afford to travel.

Played in the 28,000 capacity stadium that Ahmet Esenyl’s father helped build in Lefkosa, the matches were beamed live back to Lapland and Kosovo, but only a few hundred locals scattered the stadium. Mehmet Ali Talat was presented to the teams before games and the national anthems were played. In the case of the Sápmi they had their own, but Northern Cyprus had to make do with the Turkish anthem.

Northern Cyprus won both matches and the tournament, dubbed the Peace Cup, was a new beginning for the KTFF. A couple of months after the Northern Cyprus team had visited Lapland, the Embargoed campaign was set up by Ipek Ozerim, who had been a PR adviser to President Denktas. The plight of the Northern Cypriot footballers was a good stepping point for Embargoed. After the Monaco protests, a Balls to Embargoes poster was launched with half-a-dozen mostly London-based Turkish Cypriot players asked to strip for a poster, including former Crystal Palace player Kerem Bashkal. Put out before the 2006 World Cup, the idea was to shame FIFA into embracing the Turkish Cypriots.

Yasin Kansu of Çetinkaya, top scorer in the Northern Cyprus league in recent seasons, also took everything bar his socks off for the poster. He explained: “We voted for the solution in Cyprus and still we can’t play football with the rest of the world. In a few years, I will be retiring and if this situation continues, I will never get the chance to play against first class international opposition and know just how good I am.”

Embargoed were handed an even better PR opportunity in February 2007, when Arsenal decided to ban flags from the club’s new Emirates stadium after some fans complained about a TRNC flag being waved at the ground by a Gunners’ fan, northern Cypriot, Mete Ahmed.

Embargoed and the KTFF are trying to find a solution to a conflict that few of the generation they aim to help can remember. Since the invasion in 1974, football has changed out of all proportion in terms of popularity and commercialism and using the world’s most popular sport as a tool to reinforce the idea of a nation must seem an easy option. The KTFF must also notice with some degree of envy the improvement in the football in the south. Unlike clubs from most small nations, the professional Greek Cypriot teams always manage to get through at least a couple of rounds in European football, although no club has qualified for the Champions League proper yet. The national team is also improving and in 2007 managed to thrash the Republic of Ireland 5-2 and draw 1-1 with the previous year’s World Cup semi-finalists, Germany.

Relations are softening. The KTFF have met with the Cyprus FA in the south, but the meeting had to take place in a Hilton hotel not in the Greek Cypriot association’s offices or else it could have been deemed a formal affair and given some credence. There were some constructive talks over youth football, but the KTFF did not like the suggestion that they become part of the Cyprus FA. What they want is a new FA set up, following the British model. The KTFF invited the Cyprus FA to the north, but they have yet to take up an invite to cross the eerie border, where empty buildings full of bullet holes remain just as they were when so suddenly abandoned three decades before.

So far, the idea of a Northern Cyprus national team has yet to stir much interest among the locals. The Turkish league on television remains more popular and crowds for national team matches are very low. But for Cengiz Uzun, the KTFF’s main organiser, the future lies most definitely in a Northern Cyprus team. He explains: “It will take a little time for the people to love their national team, but we are not terrorists. We have peaceful feelings towards our neighbours, so why should FIFA put bans on our players? These are questions to be answered by the Greeks.”

The latest stunt is to protest about the Monaco government caving in to international pressure and forcing its amateur national team to cancel a match against a team representing the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, one of the world’s true pariah states that has been in virtual limbo since declaring independence from the rest of Greek-dominated Cyprus in 1983 – a move still only recognised by Turkey.The tensions between the Greek Cypriot majority and the Turkish Cypriot minority continued after independence and in December 1963 there was a violent battle in the capital of Nicosia. United Nations peacekeepers were deployed but the violence continued and Turkish Cypriots retreated to enclaves throughout the island.

In 1974, an attempt sponsored by the government of Greece to seize control of the island prompted a Turkish invasion. After a 25 day battle that left around 6,000 people dead, the Turkish troops had seized a third of the island including a large section of Nicosia – or Lefkosa, as the Turks call the island’s capital. Thousands of Greek Cypriots retreated to the south behind a hastily drawn line between the two communities, losing their homes in the process.

Prior to independence, there had been unrest between Greek and Turkish Cypriots and in 1955, according to the Turkish side, their most famous football club Çetinkaya was barred from playing a match against a Greek-Cypriot side, Pezoporikos, in the capital Nicosia. Çetinkaya Sporting Club had won the all-island league in 1952/53, but when the Turkish Cypriot clubs were expelled from the Greek Cypriot FA in 1955, their clubs formed their own association, the KTFF.