Comment

Havelange 100 years: Sports leader in disgrace, Olympic guest of honour

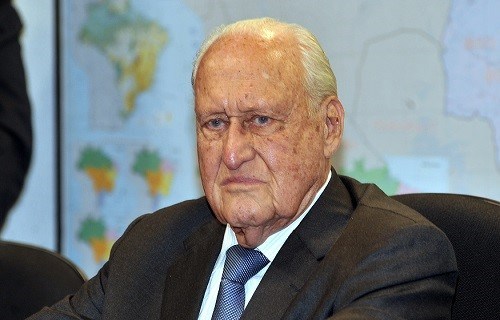

João Havelange at a 2010 commission meeting in the Brazilian senate. Photo: José Cruz/ABr

08.05.2016

One memorable moment in my usually unglamorous work with sports politics came in the early evening of Friday 2 October 2009, a few hours after the International Olympic Committee had awarded the 2016 Summer Olympics to Rio de Janeiro. Standing in the corridor between the lobby and the lifts at the Copenhagen Hotel Marriott, two men of age came towards me.

One was a 68-year old former football star, stepping lightly, almost dancing towards the lift area with a broad and delightfully happy smile on his face. His name was Pelé.

Behind him, the body slightly bent and not moving quite as fast, but advancing with dogged determination and a sinister look in his furrowed face, a 93-year old former football president moved on, his eyes set with determination of something in the distance that the rest of us did not see. His appearance was impressive, like a troll in the fairy tales, and for a moment, I felt relieved that this encounter did not take place in the dark woods where I would surely have been devoured.

As you may have guessed, the troll disguised as a fellow human being was Jean-Marie Faustin Goedefroid Havelange, better known as João Havelange, president of FIFA 1974-1998.

The two Brazilians in the Marriott corridor have a long common history. One of the most important chapters was written when Havelange and Pelé exchanged favours that would ensure power to the former and financial rescue to the latter.

This arrangement of mutual dependence is very well described in the article “Playing for power: João Havelange’s path to FIFA 1958-1974” by PhD student Aníbal Chaim from the University of São Paulo. The article also outlines how Havelange understood to exchange services with the military regime that ruled Brazil in the 1960’ies and 1970’ies so that he could mobilise support to the dictators from football while they in turn could help him with money and favours to ascend to the throne of FIFA.

Architect of a system with built-in corruption

Havelange was one of the pioneers in building up the international football business that became a source of immense wealth not only for FIFA and football but also for a great number of the individuals running football. He was a main architect and manager of a web of political and commercial interests, a system of which corruption is not an unfortunate side-effect, but by and large one of the core purposes.

This system is now crumbling, thanks to the tireless efforts of investigative journalists and thick-skinned public investigators around the world, and many of the people recruited by Havelange are now in the courtrooms or jails, if they have not escaped through the exit we all have to find at the end.

But João Havelange is still alive, and very much so. He may have fallen in disgrace and lost his positions as an IOC member and an honorary lifetime president of FIFA. But he is not forgotten by the Brazilian sports establishment who promises that he will be a guest of honour at the Rio Olympics this summer because of his important role in convincing the IOC.

On that decisive day, 2 October 2009, Havelange displayed his bold and brutal charm. After another very senior sports pioneer, the ex-president of the IOC Juan Antonio Samaranch, had told his IOC comrades that they should choose Madrid as Olympic host, so they could fulfil his last wish as he was nearing the end of his life, Havelange chose the complete opposite strategy: he invited the IOC to come to Rio in 2016 to celebrate his 100th birthday.

As Havelange’s corruption affairs have gradually become a matter of public record and the man himself pressured out of the IOC, the Olympic family may have hoped that natural forces would ensure that Havelange would never see this invitation come through.

But now, the IOC President and the rest of the IOC top leaders face an intriguing dilemma: If they accept the invitation, they accept celebrating one of the main inventors of systemic corruption in sport at a time when they are desperately trying to rid international sport of its shattered reputation. If they do not accept, they will offend their local hosts who have fought hard to rescue the 2016 Olympic from the economic and financial chaos that Brazil is currently living.

Arm-in-arm with the military regime

And the events in recent years have not broken his self-confidence; I have personally seen a letter from last year in which he still uses the envelope and letterhead paper bearing the title of FIFA Honorary President.

If there is one thing Play the Game can thank João Havelange for without being hypocrites, it is that he has been a longtime source of inspiration to pay resistance to the sports structures that he built.

We believe that we will not offend the man by highlighting one of the key personal features that has marked the destiny of his person and to a large extent also of world football: His unwavering appetite for power, and his unusual talent for acquiring it.

It is, therefore, appropriate to celebrate Havelange’s 100 years by publishing the above mentioned article.

The research is made by a young Brazilian PhD student and sports historian, Aníbal Chaim, and we find it extremely interesting. The article is much longer than those we usually bring, but it is thought-provoking reading. And you can draw a direct line from the early 1970’ies to the FIFA we know today.

Parabéns, Senhor Havelange!

More information

Read Aníbal Chaim's paper on João Havelange's path to power:

You can also watch a video with Aníbal Chaim presenting his research into relations between Havelange and the military regime during a session on the Rio Olympics at last year’s Play the Game conference: