Comment

World Cup Russia 2018: Heading towards excesses

The 12 Russian stadia to be used for the 2018 World Cup will be more expensive than the 20 stadia built for the World Cup 2002 in Korea and Japan, accounting for inflation, according to Martin Müller. Photo: Otkrytie Arena in Moscow / Wikimedia

25.06.2014

While the heart stopper finish of World Cup preparations has been keeping the world’s eyes on Brazil, troubles are brewing in the next host country. The paint is barely dry on Russia’s Winter Olympics facilities, but the nation is already gearing up to host the next mega-event. As with Sochi, which cost at least USD $51 billion, the World Cup 2018 is en route to becoming the most expensive World Cup ever.

A 2013 government act (Postanovlenie 518) fixed the minimum budget at USD $21 billion [RUB 660 billion]. That covers just the basic costs required for hosting the event: stadia, targeted transport projects, security, energy supply and so on. As the Chairman of the Organising Committee, Igor Shuvalov, remarked: “We have trimmed absolutely everything. There is nothing obsolete, not a single obsolete object. [We have kept in the budget] only what is associated with the World Cup.”

Yet, even this bare bones event comes in at almost double the current estimated costs of the World Cup in Brazil.

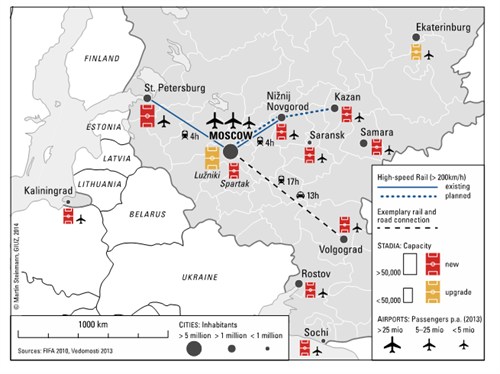

The 2018 World Cup will be held in 11 cities in European Russia from 8 June to 8 July 2018 (see the map in Figure 1). As of June 2014, only 3 out of 12 stadia were even close to completion – Moscow’s new Otkrytie Arena as well as the stadia in Kazan and Sochi. With Luzhniki and Ekaterinburg’s Central Stadium, a further two already exist but are undergoing total renovation. St. Petersburg’s stalled stadium is years from completion, and the remaining six stadia must be built from scratch, but work has yet to begin.

Figure 1: Map of stadia and of transport infrastructure for the World Cup 2018 in Russia

Construction delays and escalating costs

Russia is now facing the challenge of coordinating eight stadium projects across eight cities at the same time. This means dealing with the diverging demands of different regional elites, different contractors, different stakeholders and different urban settings.

Time pressure further compounds this situation. Vitaliy Mutko, the Russian Minister for Sports, admitted in March 2014 that construction is already behind schedule in every location: “The pace of designing the stadiums gives cause for alarm. Deadlines are being broken. There are problems in every region.” At that point, seven stadia were still in the design phase.

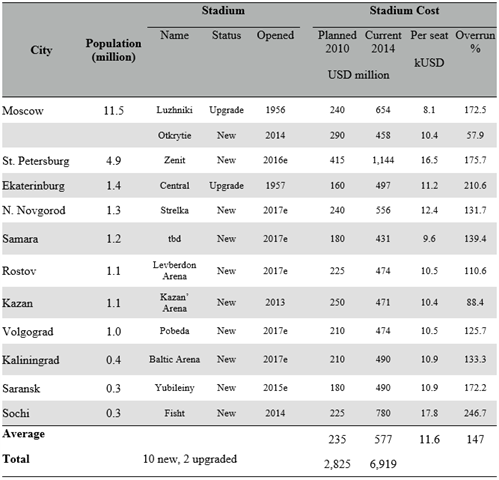

As an early sign of trouble, costs are already going through the unfinished roof. Between the bid in 2010 and June 2014, forecasts for stadium expenditures have more than doubled from USD $2.8 billion to USD $6.9 billion (see Table 1). This makes the 12 stadia more expensive than the 20 stadia built for the World Cup 2002 in Korea and Japan, accounting for inflation. And the USD $6.9 billion will not be the final estimate. In Brazil, for example, actual costs more than doubled when compared to estimates four years out.

Table 1: Stadium investments for 2018 World Cup

(Sources: Population data from 2010 census; FIFA, Vedomosti, Interfax, ITAR-TASS, Don News, gazeta.ru, Rossiya2018.rf, wc-2018.ru.; an exchange rate of USD 1 = RUB 30.6 was used for calculation; e=expected)

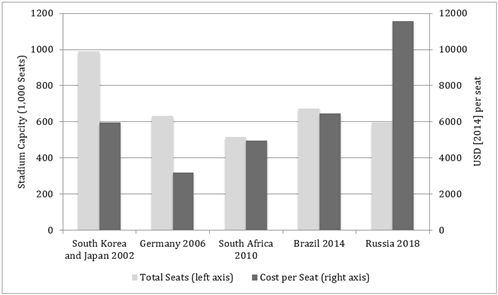

The projected costs place the stadia in Russia among the most expensive worldwide. At USD $577 million, the average cost per stadium is more than 50% higher than in Brazil and more than 3.5 times higher than for the World Cup stadia in Germany 2006 (see Müller 2014). Per seat, average costs are USD $11,600 (see Figure 2). Compare this to the average seat in a football stadium for the World Cup 2006 in Germany, which ran to about a quarter of that – just over USD $3,000.

Figure 2: Comparison of total number of stadium seats and costs per seat for the World Cups 2002, 2006, 2010, 2014 and 2018

Sources: Associated Press; Cabinet of Germany; World Stadium Index; own calculations

The largest part of the USD $21 billion, however, is scheduled to flow into various transport projects required for hosting the event: airport upgrades and links between the airports and the stadia. In addition, Russia will have to build 86 training bases, among others for the national teams.

Excess capacities

When finished, the Russian World Cup stadia will exacerbate another problem: overcapacities.

Stadium construction for the event will increase the number of stadium seats in Russia by nearly half a million. This is more than one-third of the capacity that existed in the country at the time of the bid in 2010. Yet, most Russian football stadia are already too large for the crowds they draw. The 15 clubs in the premier league use about 60% of their stadium capacities.

Moreover, going to football matches is not a widespread pastime in Russia, compared to other countries. No more than 0.14% of the population go to see a premier league game. The average number of fans per game is just under 12,000. These attendance figures place Russia at the bottom of the table among larger countries in Europe. The demand for football tickets has not grown since the early 2000s, despite increasing disposable income.

These factors make it unlikely that the investment into stadia is going to provide economic returns, raising the spectre of white elephants. Indeed, private investors or clubs have not come forward to fund the stadium construction. This disinterest from the private sector has forced the Russian state to dig into the federal budget for construction costs – just like in Brazil and South Africa.

Some of the outcomes of this building spree are nothing short of Kafkaesque. The Central Stadium in Ekaterinburg was built in 1957 in Stalinist neoclassicist style and re-opened after an USD $82 million renovation in 2011, just after the World Cup had been awarded to Russia. It is now slated to close again for upgrading for the World Cup. The projected bill: almost half a billion US-Dollars (see Table 1). In the course of the renovation, the seating capacity will expand from 27,000 to 44,000, which is far higher than forecasts for future attendance.

Since opposition candidate Evgeniy Roizman became mayor of Ekaterinburg in 2013 and ousted the incumbent from the party United Russia, the debate has become more heated. He has fuelled controversies over whether it would be cheaper and less detrimental to the protected architecture to build a new stadium rather than revamp the existing one. Roizman is even skeptical of Ekaterinburg hosting the World Cup at all: “I don’t know if it’s worth spending 12 to 15 billion [USD $390 to $490 million] for four games in Ekaterinburg. I wouldn’t hurry to open the city budget to fund an enormous international event that the city might not be interested in.”

Putin’s dilemma

If the preparations for the World Cup 2018 continue on their current path, it is clear that the mega-event will suffer from profligacy and produce massive stadium overcapacities. Every one of the stadium projects is already above budget and behind schedule. Yet, even compiling this information is difficult due to the lack of transparency: there is no monitoring of costs and no unified source of information such as a website for the public, neither is the bid book available online to compare promises against realities.

While the inefficient allocation of resources will be welcome for the elites who have a stake in the event, it also increases pressure on the state budget. The economic outlook for Russia is bleak following the crisis in Ukraine, with growth forecasts a mere 0.2% for 2014, capital flight as high as during the 2008 financial crisis and a recent downgrade of the credit rating to just above junk bond status. The Russian state can ill-afford another extravaganza of the magnitude of the Sochi Games. For Putin, this dilemma will cause headaches.

Note: This is an adapted version of Müller, Martin and Sven Daniel Wolfe (2014): World Cup Russia 2018: already the most expensive ever? Russian Analytical Digest No. 150, available from http://www.css.ethz.ch/publications/RAD_EN.

About the Author

www.martin-muller.net; martin@martin-muller.net

Further reading:

Müller, Martin (2014). Event seizure: the World Cup 2018 and Russia’s illusive quest for modernisation.

Working Paper:

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2368219