Comment

Brazil is the true world champion – of sports debate

Photo: Catalytic Communities/Flickr

14.08.2014

The moment the referee blew the whistle to end the final match of the 2014 FIFA World Cup, another whistle blew for the next, very important match: The battle to become Brazil's next president.

The widespread gibe that the 200 million people in Brazil have footballs for brains could easily lead to the conclusion that the incumbent president Dilma Rousseff, after the Brazilian team's two painful defeats in the final rounds, might as well clear her office before the election on 5 October.

But Brazilians are not the football-crazy airheads some in the outside world claim to believe, and no defeat is so big that it cannot be used as a leverage for a new agenda. A shrewd politician like Dilma knows this.

The guests from the Netherlands had hardly quashed the Brazilians’ remaining dream of World Cup 2014 success in the bronze match on Saturday 12 July when Dilma tweeted that it was time to modernise the Brazilian football world:

"The government does not want to govern football, because it cannot, and football should not be the government. We will help modernising it. [...] Football, which is a private activity, needs the best practices of private management of the commercial, financial and footballing areas." (own translation from Portuguese, original tweets here and here)

So instead of taking a rest after their successful month of staging the world’s biggest football party, the Brazilians have immediately entered into a debate on the future of both football and other sports in their country.

Because why are things going so bad for their national teams, clubs and grassroots sports system when the Brazilian Football Federation (CBF) has wads of cash and the Brazilian state supports its football system with billions of dollars each year through various public funds?

According to a group of former players, Bom Senso FC (FC Common Sense), the 24 leading clubs in the country owe 4.7 billion reais (more than 2 billion US dollars) mostly in player salaries and taxes. And while the players wait in vain for their monthly salaries, the Brazilian football managers are known for riding horses whose heights closely match the deep lack of confidence the general public has in them.

Public pain, private gain

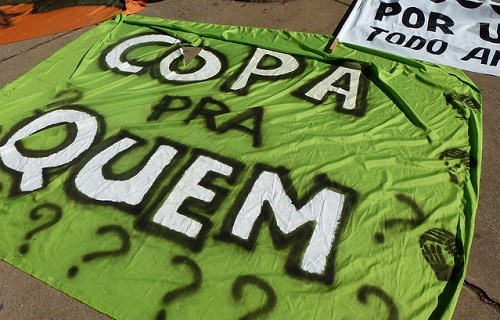

In other words, the Brazilians have once again ignited the intense sports political debate that made them world famous during the big demonstrations that coincided with their hosting of the FIFA Confederations Cup in June 2012. This debate was put on hold for a few weeks to stage “A copa das copas”, the World Cup of all World Cups.

To the world’s surprise – and perhaps their own – the Brazilians proved that they could manage the logistics and organisation of the World Cup in such a way that the tens of thousands of visiting spectators, media professionals, officials, coaches and players could spend their time on what they were there for, and not in endless queues and traffic congestion.

The Brazilians proved themselves as friendly, helpful and efficient hosts, but this aspect of their achievement is not what will be remembered. It is, after all, what would be expected of any country seeking to host one of the biggest global events.

The historical uniqueness of this World Cup is that the government, the parliament, several public organisations and large parts of the population have directly attacked the economic and political structure that supports the vast majority of global sports events: a massive transfer of public funds to private accounts.

Or, as the English saying goes: Public pain, private gain.

This effect of the FIFA World Cup was hardly expected by the organisers, and we should not expect “public debate” to appear on the first slide of the global event industry’s PowerPoint presentations.

But it should be, because the public protests and debate have set a new international agenda for sport. When most matches played during the 2014 World Cup are forgotten, we will still owe the Brazilian population thanks for having examined and debated what a huge global sporting event comprises in terms of challenges for the host country.

World Cup decision taken by a narrow circle

It is worth remembering that Brazilians have been well placed to revolt against aspects of this great football competition.

The decision that the 2014 World Cup should be staged in Brazil was made in 2007 by a very narrow circle, in which FIFA's then honorary president Joao Havelange and former president of Brazilian football and FIFA board member Ricardo Teixeira played the starring roles in close collaboration with their longtime ally, FIFA president Sepp Blatter.

It was hardly the honour of the nation that Ricardo Teixeira had in mind when he appointed himself as chairman of the World Cup Organising Committee, COL, and established a private company that would carry out tasks on its behalf: Teixeira himself held 99 percent of the shares in this company and the contract stipulated that the company's profit was not to be negotiated until after the World Cup.

But Teixeira, the COL president never got to negotiate payments with Teixeira, the company owner. In 2012, Teixeira and Havelange were forced to leave all their posts after irrefutable evidence that they had received millions of dollars in bribes in the so-called ISL affair during the 1980s and 1990s.

A key decision-maker in 2007 was, of course, the then Brazilian president Lula da Silva, whose interest in combating corruption was somewhat more relaxed than his efforts to lift millions of people out of abject poverty.

The samba whistles got a different ring to them when Lula, after the election in 2010, handed over his presidency to his chief of staff Dilma Rousseff, who within a short time sacked six ministers on suspicion of corruption, including the sports minister. Meanwhile, Dilma has been careful to keep her distance from football officials, for example, by doing her best to avoid posing for official photos with them.

Anger over white elephants

Since Dilma came into power, corruption has become a central theme in the Brazilian social debate, and the recent World Cup and the upcoming summer Olympics in 2016 have again and again been highlighted as examples of opaque and irresponsible use of public funds.

The Lula government's decision to increase the number of stadiums from eight to 12, so that the World Cup could become a national event, has led to a series of scandalous construction projects. Several of them are doomed to end up in the graveyard of the 'white elephants', because they are located in areas without a popular football team or other regular spectator magnets, and others will only survive on the abundant subsidies from the state or the municipality. The few stadiums that have the potential to be profitable in Brazil's biggest cities are in the process of being privatised.

The questionable investments have caused anger in a country where the public health and education systems often lack the most basic resources. Shortly before the World Cup, President Dilma had to reassure the population that more than 200 times the investments made on stadium construction had been made on health and education over the years.

These figures are disputed, but even if Dilma does have a point when she says that the construction of 12 stadiums does not play a major role in the huge economy of Brazil, the magnificent, high-tech stadiums stand as powerful symbols of a skewed and antisocial use of society's resources.

It only makes this symbolism stronger knowing that President Lula promised that this World Cup would be a free ride for Brazilian taxpayers. Instead, the final price tag will reach around 14 billion U.S. dollars, of which 4 billion have been spent on stadiums.

The public interest in the expenditures has been big. In October 2012, Brazilian news site uol.com.br ran a piece of news about a forecast made by Play the Game for the future use of the 12 World Cup stadiums, the article reached more than 100.000 clicks in a few hours.

And both the World Cup and the Olympics have had their very own 'transparency portals', where the government accounts for its spending.

Democratic pride

But money isn’t everything. The nation’s dignity and pride in being a true democracy have also been challenged by the agreements it has made with FIFA.

The desire to mark the country's independence was one of the reasons why the congress delayed the 'World Cup Law' meant to secure FIFA's requirements for tax exemption, legal immunity, beer sales at stadiums and other contentious issues.

The delay of more than a year exacerbated the tense relations between FIFA and the World Cup hosts, and was not only caused by the opposition and prominent members of congress such as the former soccer star Romario, who portrayed FIFA as a modern version of the European colonists.

Deep within the government's own ranks, including President Dilma herself, there has been a sense of discomfort about the aspects of the World Cup which have unilaterally fuelled FIFA’s position of power, both financially and institutionally.

The soil was in every way fertile enough to put FIFA and the World Cup at the centre of protests during the Confederations Cup in June 2013, which turned out to be the largest demonstrations in the history of the new Brazilian democracy.

Millions of protesting Brazilians made it clear that it is not acceptable to host a sports party at any cost, and that both the sports organisations as well as governments starving for attention need to take greater notice of the society at large and the people who must ultimately pay the bill and live with the aftermath.

Fear of being trapped

There can be many reasons why the protests during this World Cup have been smaller and less prominent. What has undoubtedly played a role is that many of last year's peaceful protesters and their sympathisers have feared being trapped between an unusually heavily armed and aggressive police force on the one hand and violent anarchistic rioters on the other.

But it is also worth remembering that the demonstrations last year emerged spontaneously in Brazil's major cities and were initially carried out in protest of a minor increase in São Paulo’s bus ticket prices. It was not a well-planned first scene of a script meant to reach a climax during the World Cup.

In addition, the Brazilian politicians, led by president Dilma, managed to create the impression that the demands of the people were being heard and understood.

Finally, it was probably also an issue that the vast majority of Brazilians wanted to show their friendly side while the country was filled with visitors from across the world. The World Cup should – in addition to all the conflicts that are associated with it – also be a celebration, particularly in a country that has learned so much about itself through football.

There is no reason to complain; on the contrary. A turbulent and violent World Cup could have further polarised the Brazilian society and have added to the power of the security enforcers.

It could also have increased the international sports organisations’ appetites for placing their big events in authoritarian regimes where they do not waste time on debating how to spend people's collective funds and where processions in the streets most often take place in the form of tributes to the nation's great leader and glorious history.

The spotlight turns to the Olympic leaders

The International Olympic Committee, which is responsible for the next global event staged in Brazil (Rio de Janeiro) in just two years’ time, can take a deep breath: The Brazilians have shown that they can actually deliver construction projects on time, even though it may look like a lost cause along the way, and that an explosive political situation does not necessarily lead to explosions.

Any talk of a Plan B for 2016 is now likely to have been silenced after the World Cup. But the situation is not without risks. The Olympic facilities are still less than 40 percent ready, and both the contractors and workers’ unions are aware that time constraints provide good opportunities for additional revenue.

The venue for the Olympic sailing events is so densely polluted that you can almost walk on water, but not without getting your feet dirty.

And locally in Rio, the public protests could start again when the government continues its cleansing policy in the favelas – a policy that is not just pushing organised crime out of Rio's central districts, but also large populations of poor people.

But the Olympic leaders cannot sleep like babies. The spotlight, which is currently aimed at football leaders, will soon be turned towards the Brazilian Olympic Committee (COB), which has failed to turn the more than doubled government subsidies – from 2008 to 2012 a total of 1.5 billion dollars per year – into visible progress in elite sport. Although the funding will rise in the time leading up to the Olympics on home soil, not many Brazilians believe that the country will reach its goal of being among the top ten in the medal standings.

Since many of the Olympic participants have to pay for training equipment and travel expenses themselves, more and more athletes are expressing their concerns about where the money ends. Allegations of corruption exist in many other national sports federations, including the volleyball federation.

It is safe to assume that the government will let the Olympic sports leaders be until after the 2016 Olympic Games, in order to avoid risking further delays.

But if fundamental reforms of the national Olympic committee and the major sports federations are carried out afterwards, the Brazilians will no longer will not only be able to call themselves the world champions of sports debate.

Then they deserve a gold medal for the best democratisation of sport.