Transforming Rio - For the benefit of whom?

By Christopher Gaffney, Department of Geography, University of Zürich

Excerpt of article from ICSSPE’s Bulletin no. 70/2016 – see further reference at the bottom of the page.

One of the justifications deployed for hosting the Olympic Games is that they will offer transformational benefits for metropolitan areas. The extensive upgrades to physical infrastructures that accompany the colossal event are wrapped in the discursive framework of “legacy” – a word that carries positive connotations in social, economic, and physical realms. However, empirical evidence for lasting, positive effects of sport mega-events is sorely lacking (Bass, Pillay, & Tomlinson, 2009; Horne & Manzenreiter, 2006; Porter, Jaconelli, Cheyne, Eby, & Wagenaar, 2009).

This article will examine two major urban interventions that have been undertaken in Rio de Janeiro as the city has prepared for the 2016 Summer Olympics: the extension of the city´s metro and the privatisation of the port region. I will demonstrate that these “legacy” projects have not had positive effects for the city as a whole, but have rather decreased transparency in government, increased socio-economic inequalities, privatised public space, and torqued urban planning agendas to stimulate real-estate speculation and Games-related transportation agendas to the detriment of more equitable long-term planning.

Bait, switch, execute

In evaluating the projects undertaken, the proposed budgets, and eventual Olympic realities we must begin any investigation of Rio 2016 with the bid books that were presented to the IOC in 2009. Following the corruption scandals surrounding the Salt Lake City Olympic bid, IOC members were forbidden to conduct site visits prior to voting on Olympic candidacies. Thus, the only information that many of the voting members had about the Rio 2016 bid would have come from bid books and candidacy presentations at IOC meetings. While this shift in policy may have served to prevent a repeat of previous corruption scandals, the lack of real-time information about existing urban conditions may have been a contributing factor in the IOC´s decision to award the Games to Rio de Janeiro. The city is incredibly photogenic, but chronically dysfunctional. In order to understand the trajectory of the metro and port region projects, it is instructive to examine the contents of the Rio 2016 bid books for a number of reasons.

The first reason is to analyse the projects that the IOC has accepted as satisfactory for Games operations. While each edition of the Games has inevitable adjustments to major infrastructure projects, the general Games plan as outlined in the bid books can be considered a candidate city´s enticement to the IOC – what I am calling “the bait.” Bid books present an idealized Olympic City that will appeal to the aesthetic tastes, functional necessities, and discursive predilections of the IOC (Kassens-Noor, 2012).

A second reason to examine the bid books is to analyse the promised benefits to the resident population, or the “legacy” that public monies will deliver after the Games have gone. In this way we can hold the Games coalition accountable for the (non-binding) promises that they have made vis a vis the candidacy files and will be able to analyse more rigorously the eventual deliverables in terms of cost, functionality, opportunity cost, and public use value.

Third, by looking closely at the bid books, we can then compare the shifts in the Olympic project over time, uncovering these changes within a broader chronology of Games preparation. This is what I call “the switch”.

And finally, while the bid books do not indicate processes of planning, contracting, financing, and construction, by tracing the evolution of Olympic projects from their origins in the bid to their physical presence on the urban landscape, we can identify process of dislocation, corruption, legal exceptionality, and rule by decree. This is the “execute” phase, in which we have seen innumerable instances of human rights violations, police violence, and executive orders that have displaced tens of thousands from their homes in the name of Olympic preparedness (Comitê Popular da Copa e Olimpíadas do Rio de Janeiro, 2015).

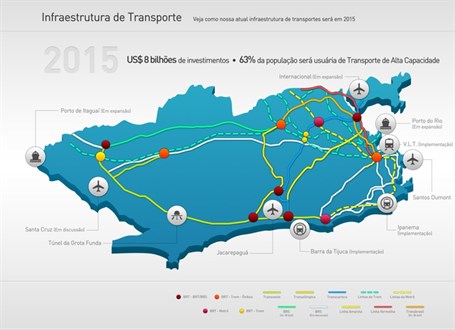

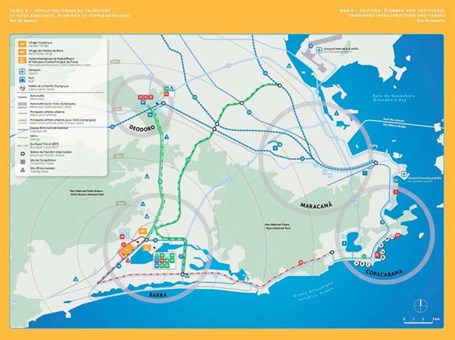

The Rio 2016 Bid Book contained a transportation plan that was designed to link four Olympic clusters: Copacabana, Barra da Tijuca, Maracanã, and Deodoro. In the bid book, the plan was to extend Rio´s metro line to Gávea, just past the beachside neighborhoods of Ipanema and Leblon and then to build a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) line that would link Gávea to Alvorada station in Barra da Tijuca.

Figure 1 and 2. Transport infrastructure as presented in the bid books.

The second major intervention planned was to construct a BRT line (called the Corredor T-5) between Alvorada and Penha, in Rio´s Zona Norte. The final planned new roadway was labelled the BRT Ligação C, which would connect the Deodoro Olympic cluster with Barra da Tijuca. The remainder of the Olympic transportation would occur along existing roadways with so-called “Olympic lanes” forming a “high performance transport ring” around the city (Rio 2016, 2009). The Olympic transportation plan was building upon the system that had been put in place for the 2007 Pan American Games, which had linked four games clusters through dedicated traffic lanes taken out of circulation from the general public. On April 27, the Olympic operational plan declared 260km of Olympic lanes for exclusive use by the “Olympic family” [sic], security and emergency services.

The Port Region was mentioned only once in the Rio 2016 bid book, and there was no indication that the Olympics would have a significant presence there.

Not long after Rio had signed the hosting agreement with the IOC, all of these plans changed. No longer would the Metro extend to Gávea, but would only go as far as Jardim Oceânico at the extreme eastern end of Barra da Tijuca. All plans for concluding the previously planned extensions of the metro system were dropped. Additionally, the BRT line linking Alvorada and Penha was extended, at a cost of more than R$500 million, to connect with the Tom Jobim International Airport. The Transoeste and Transbrasil BRT lines were added to the Olympic transportation plan, key elements in the largest reorganization of transportation in the city´s history.

In addition to shifting the Olympic (and by association, metropolitan) transportation network, within weeks after winning the bid, Rio 2016 changed its overall Games proposal, asking the IOC that several sporting and housing venues be moved to the Port Region (Costa, 2010).

The IOC denied these requests, but the shift in public policy was made explicit when mayor Eduardo Paes decreed the entire Port Region (5 million square meters) an Area of Special Social Interest (Gusmão de Oliveira, 2015, pp. 224–226). This opened the way for one of the largest privatisation projects in the Americas, one from which some of Brazil´s largest civil construction firms would profit from the ceding of public territories, infrastructure development, and real-state speculation (Rolink, 2011).

Metrô

One of the defining characteristics of Rio de Janeiro´s transportation system is that there are no conveyances that are operated by the city itself. Rather, each of the transport modalities (train, ferry, metro, highway, and bus) is operated through a long-term concession. INVEPAR has operated Metrô Rio since 2009 through the “Concessão Metroviária Rio”. As part of this concession, legalized in the same year as the Olympic decision, Metrô Rio (INVEPAR) had as a part of its contract the right of first refusal to build any future extensions to the metro lines under concession.

INVEPAR’s holding of the concession under these conditions was not unusual in the context of the city´s transportation structure, but their undue influence over decisions regarding the future of the city´s metro system would have significant consequences.

The decision to extend the metro to Barra da Tijuca was highly controversial, as many urban planners and engineers had long called for alternative metro lines that would more completely build a transportation network in a notoriously disconnected city. The originally planned Olympic extension of the metro to Gávea would have permitted the pursuit of these previous plans, allowing for an eventual linkage with metro stations that were built in the 1970s but never opened. The creation of a network instead of the extension of the one line would have contributed to the development of a more robust system. The argument of those who came out against the extension of Rio´s metro to Barra da Tijuca was that it would primarily benefit residents of the wealthy Zona Sul and Barra da Tijuca, and the Olympic project would delay the development of other, more necessary and previously planned lines by decades.

Several civil society movements and opposition politicians voiced their concerns about the Olympic transportation plan, but to no avail. As the metro is owned by the State of Rio, the decisions about contracts, concessions, and construction come from the governor´s office. The law firm of Coelho, Ancelmo, and Dourado represented INVEPAR in its dealings with the state. The wife of then-governor Sérgio Cabral, Adriana Ancelmo Cabral, was a principal figure in the negotiations (Junqueira, 2010). The extension of the metro to Barra da Tijuca as part of the Olympic transportation project was not put out to public tender and INVEPAR won the non-competitive bid to build and manage what became known as “Linha 4”.

As the wife of a sitting governor helped INVEPAR to put together a proposal to extend the metro by 23 km, they brought together some of Brazil´s biggest construction firms into a consortium called Rio Barra S.A. to undertake the construction.

Queiroz Galvão Participações - Concessões S.A., Odebrecht Participações e Investimentos S.A. and Zi Participações S.A together with INVEPAR convinced the State of Rio to seek R$7.5 billon in financing from three institutions: Agência Francesa de Desenvolvimento, Banco do Brasil and BNDES, Brazil´s National Development Bank.

Odebrecht and Quieroz Galvão have been at the epicenter of the Lava Jato corruption investigation in Brazil and in 2015 the CEOs of both companies were convicted of corruption, money laundering, and criminal association and are currently in federal prison. Their companies, however, remain part of the consortium and are still receiving state monies for the project.

Inevitably, costs increased and the project hit delays (Magalhães, 2012). In March of 2016, the Rio state government had run out of money for the final phase of construction and was seeking an emergency R$1 billion in financing so that the metro extension could be completed. As of this writing, it is unclear whether or not the metro will be operational for the Olympics.

Regardless, the project has been shrouded in controversy since its implementation, has come at a tremendous opportunity cost for the development of a more integrated transport system. Additionally, the debt burden of the State of Rio increased dramatically in the period 2009-2016, largely as a result of financing transportation, hotel, sporting, and security infrastructure related to the Olympic Games.

In early 2016, the Rio State government resorted to parceling out R$1.8 billion in salary payments to public servants and has begun to close health clinics citing a lack of funds in the midst of Brazil´s worst recession in living memory (Lobianco, 2016). Students and teachers have occupied more than sixty public schools as they fight against budgetary cuts (Nitahara, 2016). In total as of this writing, the government owes R$19 billion for the Linha 4 metro project that was originally budgeted at R$5.6 billion (Dutra & Lima Neto, 2016). Fearing that it will not be operational for the Olympics, in February of 2016, mayor Eduardo Paes suggested that the IOC strongly consider alternative transportation solutions for tourists.

Continue reading

If you want to continue reading, Play the Game readers get exclusive free access by first logging into ICCSPE’s Membership area at https://www.icsspe.org/user/login .

Please enter username: CUHK and password: 9unwtVMh. This log-in will be valid until October 31, 2016.

The latest Bulletin is offered in the drop-down menu under “Membership”.