New report documents worker exploitation in 2018 World Cup Stadiums

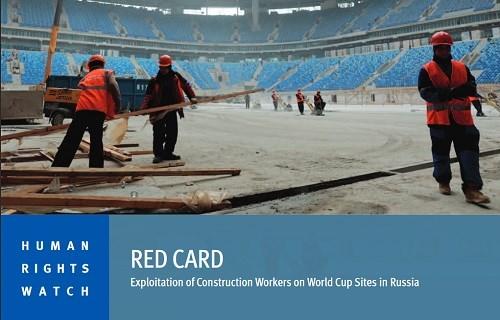

Front page of the Human Rights Watch report "Red Card. Exploitation of construction workers on World Cup sites in Russia".

15.06.2017

By Stine AlvadExploitation, no contracts, late or no payment, extreme weather conditions and fear of reprisals for speaking up against poor working conditions are some of the findings that Human Rights Watch (HRW) made through interviews with 42 workers at seven construction sites for the FIFA World Cup 2018 in Russia. The findings are presented in a report entitled "Red Card. Exploitation of construction workers on World Cup sites in Russia".

Since spring last year, FIFA has pledged to improve its efforts in securing human rights in relation to football activities, but according to Jane Buchanan, associate Europe and Central Asia Director in HRW, FIFA is not living up to its commitment.

“FIFA’s promise to make human rights a centerpiece of its global operations has been put to the test in Russia, and FIFA is coming up short,” Buchanan says in a press release from HRW. “Construction workers on World Cup stadiums face exploitation and abuse, and FIFA has not yet shown that it can effectively monitor, prevent, and remedy these issues.”

HRW specifically points to the lack of documentation on how FIFA handled the information about North Korean workers, who, according to a report in Norwegian football magazine Josimar, were working on the sites under “slave-like” conditions. Following the report, FIFA president Infantino acknowledged “incompliances” at the sites and stated that FIFA condemns the “often appalling labour conditions under which North Korean workers are employed in various countries around the world”, writes The Guardian. Together with Russian authorities, FIFA has initiated a programme to monitor the working conditions on the World Cup stadium construction sites.

However, no information about which steps were actually taken to protect these workers have been publicised, the HRW press release reads.

“FIFA and the Russian government took a notable step in organizing labor monitoring on World Cup stadiums, but to be credible, FIFA needs to make public detailed information about its inspections, what inspectors have found, and the actual results, if any, for workers,” Buchanan says. “There could not be a better time for FIFA to move away from the secrecy that has plagued its operations and to show it can achieve meaningful protections for workers, and be transparent and accountable.

Report does not correspond with FIFA assessment

In a statement issued about the HRW report, FIFA says that HRW’s “objective to ensure decent working conditions on FIFA World Cup stadium construction sites” is shared. FIFA also states, however, that “the overall message of exploitation on the construction sites portrayed by HRW does not correspond with FIFA’s assessment” and refers to a letter sent to HRW prior to the publishing of the report.

In the letter, FIFA details the work done in terms of monitoring and expresses “disappointment” that HRW chose not to share results of their research before and details the work done in terms of monitoring. Data collected up to 11 months prior to the release of the report “will naturally be very difficult and in most cases impossible to address and even remedy potential adverse impacts,” FIFA writes.

FIFA publishes human rights activity report

A step in FIFA’s declared process to “embed respect for human rights throughout the organisation” was the commissioning of a report by Harvard Professor John Ruggie in April 2016 evaluating FIFA from a human rights perspective. This week, the world governing body of football issued a human rights policy and an ‘activity report’ that describes and assesses FIFA’s efforts in the area since the release of the Ruggie report.

“FIFA recognizes its obligation to uphold the inherent dignity and equal rights of everyone affected by its activities,” the introduction to the FIFA Human Rights Policy says and promises to respect “all internationally recognized human rights and (..) strive to promote the protection of these rights”.

The policy itself consists of four pillars: Commit and embed, identify and address, protect and remedy and engage and communicate.

According to the activity report, FIFA’s most ‘salient’ human rights issues can be sorted into three categories: event related, football governance related and in-house related issues.

In his 2016 report, Ruggie concluded that an all-encompassing cultural shift was required for FIFA to live up to the recommendations given in the report that outlined 25 points of reference for FIFA to embark on in the work towards better adherence with human rights.

Since then, four of the 25 points of reference have been fully implemented, says a new report from FIFA outlining both the strategy in the work with human rights as well as the progress achieved since human rights came on the agenda at the governing body of football.

Among the achievements is the hiring og a Human Rights Manager and appointment of a Human Rights Advisory Board.

Like Human Rights Watch’s Jane Buchanan, Children Win, an organisation working for children’s rights in relation to big sporting events, also calls for more transparency and accountability from FIFA in the way human rights issues are dealt with.

“We welcome this activity update,” Marc Joly from Children Win says about FIFA’s release this week, “but are asking FIFA to show greater transparency, and to become more accountable for the actions they are taking to safeguard human rights concretely on the ground - and not only by changes on paper.”

More information

HMW report: Red Card. Exploitation of construction workers on World Cup sites in Russia

HRW press release: Russia/FIFA: Workers Exploited on World Cup 2018 Stadiums

FIFA statement on HRW report

FIFA Human rights activity report

John Ruggie report: "For the Game. For the World." FIFA and Human Rights

Children Win statement on FIFA Activity report: FIFA must provide more evidence of progress on human rights