The Fixers and the Officials

South Africa versus Colombia, May 27, 2010. According to reports from officials, this match was most likely fixed. In this artivcle, Declan Hill reveals close ties between the fixers and officials. Photo: Salymfayad/Flickr

16.06.2014

By Declan HillIt was a symbolic game - South Africa versus Colombia, May 27, 2010. The game took place a few days before the World Cup, it was in the beautiful new stadium at Soccer City in Johannesburg. The South Africans before a raucous crowd of vuvuzela-totting fans won 2-1. The stadium, indeed the entire event, was a sign that a new South African was ready for the international stage. It seemed to show that this was a South Africa that had emerged from apartheid to become a prosperous, multi-cultural society. It was a wonderful day for sport and society.

The only problem was that the game was probably fixed.

These are the words of key officials in the South African Football Association (SAFA). They point out that the referees of the game were appointed by a group of fixers from Singapore. They point out that it is very rare to have all three goals in a top match scored by penalties. They point out that the decisions leading to the penalties were questionable. And they point out that one of their own - a SAFA official - had been corrupted by the fixers and was working with them.

This story is much worse than any previously reported match-fixing scandal. For it is the clearest example that the gangs of fixers have progressed far beyond corrupted referees or dodgy players. The fixers have, at times, gone into the offices and boardrooms of the top officials who organize the sport. Many football matches were fixed with the active connivance of top-level soccer officials: the very people who FIFA is now entrusting with the protection of their sport.

This shocking development has emerged from a number of court trials, police investigations, and confidential interviews with members of the fixing gang and statements of the fixers. Now a confidential FIFA investigation report into matches played in South Africa just before the start of the last World Cup shows how the fixers went far beyond anything previously suspected: match-fixers were helped with the active connivance of high-level soccer officials.

The School for Fixers

There is one central hub for the most prominent match-fixers in the world: Singapore and Malaysia. We know about one particular group led by Tan Seet Eng - or Dan Tan – and his infamous associate - Wilson Raj Perumal. They learned their trade in an informal school for fixers in Singapore. In the early 1990s, Tan, Perumal and dozens of similar men would gather in the stadiums where the illegal bookmakers would take bets on the joint Malaysian and Singaporean soccer league.

These bookies were so successful that a Malaysian Cabinet minister estimated that they fixed over 70% of the matches. Eventually, the league collapsed and the two countries ended up in a diplomatic row.

The fixers do not have an established hierarchy like traditional American organized crime: there are no Capos, Consiglierei or foot soldier ranks. Rather the model, according to interviews with the fixers and their associates, is more like a shark frenzy. At the bottom rung are ‘runners’ – low agents who literally run back and forth between the players/referees/officials and the actual fixer who is betting the money on the fix. In the international fixes these fixers defraud the gambling market – the vast, unregulated sports betting world run out of Asia. Their local partners - in Europe, Africa, Latin America or Australia – fix the actual games by working essentially as their runners.

Above the fixers are influential businessmen with the money to back the more expensive fixes and the protection muscle to make sure the network runs smoothly. These men are mostly Asian, however, in the last few years a group of Russian criminals has joined the syndicate. Little is known about this group as they generate such fear. Three years ago, one of the European fixers told the police officer who interrogated him, “I will tell you everything, except the Russians [sic]. If I talk about the Russians I will die.”

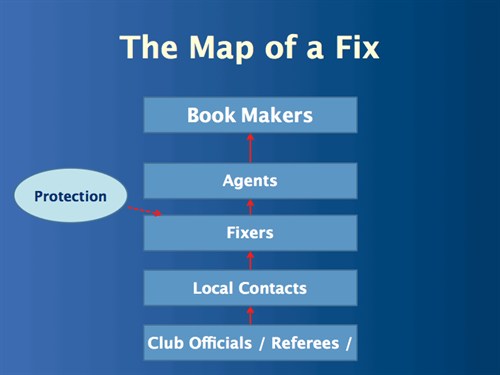

Diagram of Dan Tan's network (c) Declan Hill

Using these methods, the syndicate has fixed games around the world. Fifteen El Salvadorian players were banned for life after they were discovered to have fixed several national team matches – including one against the USA. In Finland, a group of Zambian players were playing for a local team, but taking their orders from the fixers to win or lose. In Central America, one of the group’s runners – Gaye Alassane – was named in the press as corrupting players.

It is the same situation in dozens of different countries like Croatia, Czech Republic, Slovenia, Slovakia, Turkey, Greece, Canada, Germany, Belgium, Switzerland, Austria, Lebanon. In Italy, the fixing syndicate was so powerful that more than 20 teams are under police investigation for fixing.

The fixers did not stop at buying up players and referees – they even organized their own tournaments. In February 2011, the syndicate arranged one of the strangest tournaments the soccer world had seen – or rather not seen. It invited the national teams of Estonia, Bulgaria, Bolivia and Latvia for an international tournament in Turkey. The games were played in near-empty stadiums. They were not televised. There were no fans. The games, however, were being bet on in the Asian gambling market.

The games were some of the strangest every played: every goal in them were scored by penalties – awarded by referees that the fixers had flown in for the tournament. These referees have subsequently been banned by FIFA.

The Officials and the Fixers

The real worry to the soccer world is that using these methods the fixers moved far up the hierarchy – well-past corrupted players and referees – to some of the very soccer officials who organize the sport. Many of the officials are innocent dupes of fixers like Perumal and Dan Tan who were excellent at insinuating themselves.

Photo: Michael Essien (left) with Wilson Raj Perumal.

For example, at the end of the confidential FIFA South Africa report are two extraordinary photos. The first is Wilson Raj Perumal – the man responsible for getting the fixers into the South African Football Association – standing beside Michael Essien an international star-player for Ghana, Chelsea and now AC Milan. The second photo is of Gaye Alassane, one of the runners for the Dan Tan group, was arrested in Singapore, with the man who heads up European soccer – Michel Platini.

To be clear – Platini and Essien are completely innocent of any corruption and have never been suspected of fixing a match. Michel Platini’s UEFA has led the soccer world in implementing anti-match-fixing measures. Michael Essien’s integrity is unquestioned and his meeting with Wilson Raj Perumal seems one of those completely innocent shots taken in a hotel lobby. Yet the photos show the extraordinary access the gang was able to achieve inside international soccer. They posted these photos on the Internet as a way of showing their ability to meet top-level people in the sport.

Photo: Michel Platini (right) with Gaye Alassane

In some cases, however, the fixing allegedly goes much deeper than tourist photos with famous people. In one case, Greek prosecutors when they arrested over-ninety players, referees and team owners announced that the syndicate had thought of buying an entire team in their league to have them fix on command.

Testimony of the former Team manager.

From the official inquiry report into match-fixing in the Zimbabwean National Team.

According to an official Zimbabwean soccer association report, in that country the Singaporean fixers did not stop at buying a team or an occasional game, the fixers ran practically the entire organization. The report shows the fixers led by Dan Tan and Wilson Raj Perumal were working closely with dozens of players, coaches, but most importantly, a number of senior football executives and officials.

The report states that the fixers control of the organization was so complete that in one game, Wilson Raj Perumal went into the dressing room at half-time, told the coach to sit down and instructed the team how they were going to play the second half to make money for the fixers.

It is the same method that Perumal claims that he used in arranging the referee for the Egypt vs. Australia game later that year: “You go there and meet my guy [added emphasis] in the Egypt FA… I’ll call him to anticipate that you are on your way there; he’ll be waiting for you. Just try to convince the FA to use our African referees in the Egyptian League and the Bulgarian ref in the Egypt vs. Australia game.”

Perumal writes of his work in a flawed, but fascinating, self-published autobiography called Kelong Kings [Kelong is a Malay slang word for fixing. One of the flaws of the book is that it claims to be the confession of ‘the world’s most prolific match-fixer’. Perumal was very far from that title. However, it is a great perspective into the gang and I strongly recommend the book].

While in this case it is not clear that the Egyptian official knew of the corruption involved. It was abundantly clear in South Africa days before the last World Cup, that a soccer official was actively helping the fixers. These are not just the words of members of the fixing gang, but the words of a FIFA investigator who wrote a previously confidential report into the scandal.

Fixing Before the Last World Cup

According to the confidential FIFA report, the match-fixers were not just fixing games in South Africa days before the start of the last World Cup. They had help from some – as yet unknown – South African soccer official.

These officials worked in the very organization that was putting on the last World Cup tournament in South Africa. Two years later, according to the FIFA report, Dennis Mumble then-Chief Operations Officer of the South African Football Association (SAFA) pleaded for an outside investigation. He is quoted in the FIFA report saying, “…before he could implement changes within SAFA, he needed to make sure that the organisation was free of corruption.”

After a brief investigation the FIFA team found that some South African officials were working with the fixers. The report states “… This inevitably leads to the conclusion that several SAFA employees were complicit in a criminal conspiracy to manipulate these matches.”

All the South African officials interviewed admitted that Dan Tan and his people had been working with the association to organize a set of matches that senior soccer official now think were fixed. The South Africans say that the fixers were walking up and down the hallways of their national soccer stadiums. What no one will admit to is who invited the fixing gang into the South African Football Association.

Page 43 of FIFA Report into Match-Fixing in Pre-World Cup 2010 International Friendly Matches in South Africa.

The existence of a corrupt soccer official inside the South African soccer association is also echoed by Wilson Raj Perumal in Kelong Kings, he says, “I had a SAFA official on my pay-roll I paid him $10,000 for every game.”

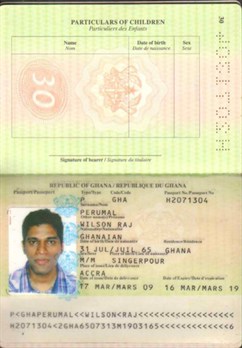

After the exhibition matches were over and the last World Cup started – Wilson Raj Perumal did not leave the country. His passport states that he stayed in the county for another three weeks.

FIFA made no investigation into his – or any other member of the gang - activities during the World Cup.

Photo: Wilson Raj Perumal's passport

In his autobiography, Perumal speaks openly about approaching other referees at the tournament. “While the World Cup progressed, I did try to approach a couple of referees [sic], but my attempts were unsuccessful… I approached a referee who had already worked for me and who went on to officiate two World Cup matches. I offered him 400 thousand dollars for each of his matches, but due a previous misunderstanding, he thought that I had a loose tongue and refused my offer.”

However, it gets worse, much worse - in in the FIFA report and separate interviews, a former-South African Football Association official Adeel Carelse says that the connections between the fixers and key officials inside SAFA carried on after the World Cup was over.

In January 2011, a match was arranged in Johannesburg between the under-23 teams of Egypt and South Africa. Carelse saw both a potentially corrupted referee and members of the fixing gang at a pre-match SAFA function. He reported his concerns to his bosses and arranged for a referee unconnected with the fixers to be officiate the game. Carelse says that he was then misdirected to another stadium by a SAFA official and had to drive frantically across the city to replace the referees at the last moment.

FIFA knows

FIFA – the organization that runs the World Cup and international soccer – knows about this problem. In October 2012, Ralf Mutschke, the Head of FIFA Security, submitted the report to the South African Football Association. A bizarre and complicated process followed. First, some SAFA executives suspended many of the people named in the report, including Dennis Mumble who had been the person who had started the investigation.

Then a South African elite anti-corruption unit ‘The Hawks’ announced that they too had been conducting an investigation and that some official inside SAFA had allegedly accepted an $800,000 bribe from the fixers.

Other sports officials called for an investigation to get to the bottom of the affair and all seemed to be heading in that direction, when the South African Sports Minister Fikile Mbalula intervened and all SAFA officials were reinstated. In the Spring of 2013, the Sports Minister and a previously suspended official flew to Switzerland to say that FIFA was welcome to investigate the matter so long as they did not ask questions about why SAFA had been so short of money just before the start of the world’s biggest sporting tournament and all the billions of dollars that the government had spent on the World Cup.

After this meeting all investigations went into a bureaucratic limbo until the President of South Africa Jacob Zuma officially announced that there would be no investigation into which SAFA official had helped the fixers. When asked the reason for this decision Zuma’s spokesman responded, “He is the President. He does not have to give his reasons, he just states his decision and that is that.”

Currently, SAFA headquarters, next to Soccer City where the Colombia match was played, is festooned with paper notices asking players or referees to report any fixing attempts to a SAFA-sponsored anti-corruption hotline. Quite why anyone would trust SAFA, knowing that some their officials have been named for working with the fixers, is not known.

In January of this year, Ralf Mutschke, the Head of FIFA Security, finally admitted the danger posed to international football by match-fixers. In a wide-ranging interview with the newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung, Mutschke had the courage to admit that match-fixers may be at the Brazil World Cup in 2014, they may approach players and teams and that certain key matches (third games in the opening round) may be in serious jeopardy. He outlined a number of measures that FIFA will take to protect the credibility of the sport. However, all of the new FIFA measures depend on the active help of national soccer officials – the very people whom the South African and Zimbabwean reports show to be vulnerable.

David Larkin a copyright lawyer in Washington D.C. who co-founded the group Change FIFA, believes that this strategy means problems for the world’s game: “This is an impossible position to reform soccer. It is a conflict of interest when some of the people alleged to be involved in fixing will potentially be working to clean it up.”

In April, Perumal was re-arrested in Finland for a new set of scandals. He faces extradition to Singapore. Last year, Singaporeans finally got around to arresting Dan Tan. However, he was not detained as a match-fixer but under an obscure anti-terrorist legislation. Tan has been locked up in indefinite detention with no scheduled trial, so potentially the public will never hear how far the corruption may have extended into the ranks of the soccer hierarchy.

More about Declan Hill