Analysis

Athletes’ gestures are protected by international human rights law

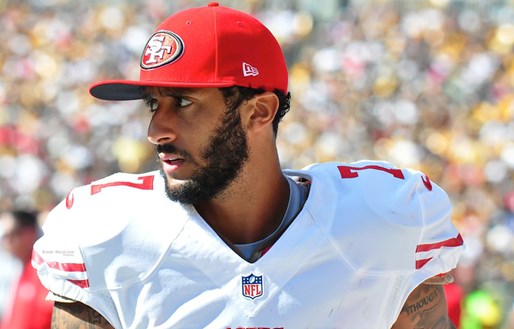

Former NFL player Colin Kaepernick's football career practically ended after he knelt during the US national anthem. Photo: Brook Ward/Flickr

11.08.2020

The recent global uproar against racism and discrimination, triggered by the death of George Floyd, immediately found its way into the world of sports and raised questions about the right to freedom of speech for athletes on the playing field.

Athlete activism and the struggle of athletes to enforce the right to freedom of speech has frequently met with retaliatory acts by sport governing bodies who are claiming to be advocates of neutrality of sports and prohibit any type of gestures on the field of play.

For example, in July 2020, Gwen Berry, the US hammer thrower who raised her fist on the podium during the 2019 PanAm Games in Lima, told Yahoo Sports that she was the victim of such retaliations by USA Track and Field Foundation, when she was not chosen to be awarded a grant. As we go back into the history, more names can join this list from Colin Kaepernick whose football career practically ended after he knelt during the national anthem of United States, to John Carlos and Tommie Smith who were immediately sent back home from the Olympic village when they raised their fists on the podium during the 1968 Mexico City Games.

The violent incidents during the protests led to calls for more peaceful protests, and the role of athletes in speaking about social issues was debated again. Some sport governing bodies such as the National Football League (NFL) and FIFA have tried to adjust their previous stances and show a more flexible approach towards athlete activism and their proper use of the platform provided by sports.

But there are still ambiguities about the issue of the right of athletes to free speech with questions such as: What does the right to freedom of speech and expression entail? Who are the subjects of this right? Is it an unbounded right or there are boundaries to it? Is the right to freedom of speech and expression subject to restrictions? If yes by whom? To what extent?

All athletes enjoy the right to freedom of expression

This short article tries to answer these questions from the international human rights law perspective. The importance of this standpoint is that international sport is practiced transnationally and is usually subject to multiple jurisdictions at the same time. International human rights law is a set of universally recognized, interdependent, inalienable rights for all human beings that – as set out in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) – apply “without distinction of any kind, such as race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status”. The law is recognized by an overwhelming majority of States.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and subsequently the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) have recognized the right to freedom of speech and expression. Article 19(2) of the ICCPR provides:

2. Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.

3. The exercise of the rights provided for in paragraph 2 of this article carries with it special duties and responsibilities. It may therefore be subject to certain restrictions, but these shall only be such as are provided by law and are necessary:

(a) For respect of the rights or reputations of others;

(b) For the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public), or of public health or morals.

Therefore, first and foremost, this right belongs to everyone. All individuals, athletes included, regardless of any characteristics or factors, do enjoy the right to freedom of expression. It is also the individual, who decides what venue to use for the purpose of the speech.

Athletes’ gestures are protected by international human rights law

The UN Human Rights Committee (HRC), the treaty body responsible for monitoring the implementation and enforcement of ICCPR, has issued a General Comment on article 19 to clarify different aspects of this right.

In the view of the HRC, the right to freedom of expression “includes political discourse, commentary on one’s own and on public affairs, canvassing, discussion of human rights, journalism, cultural and artistic expression, teaching, and religious discourse”.

The forms of expression encompass “spoken, written and sign language and such non-verbal expression as images and objects of art”.

The right to freedom of speech is not limitless though. Article 20 of the ICCPR prohibits propaganda of war and hate speech. Furthermore, this right is respected as far as it is not a threat to the rights and reputations of others or undermines public order, morals or national security.

Any restrictions on individuals should only be prescribed by law and any type of “traditional, religious or other such customary law” cannot be a justification for restricting free speech. The law should be as specific as possible with clear guidelines on types of prohibited speech and “may not confer unfettered discretion for the restriction of freedom of expression on those charged with its execution”.

One crucial point is that exceptions to this right cannot be used as justifications to block advocacy for democracy and human rights, since discussion of human rights is one of the strictly protected forms of freedom of speech.

Athlete’s gestures is one form of non-verbal communication that is protected in international human rights law, and there is little doubt that gestures such as raising a fist or kneeling during a sport event are aimed to denounce racism, discrimination and inequality which are values firmly enshrined in international human rights. At the same time, the gestures encourage racial equality, tolerance and inclusion, which are values that sport governing bodies are claiming to promote.

Transnational sports entities are bound by international human rights law

Gwen Berry’s claim came just a few days after the publication of a new report ‘Intersection of Race and Gender Discrimination in Sport’ from the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to the UN Human Rights Council. The report follows up on concerns expressed by the UN Human Rights Council over the impact of sport regulations on the enjoyment of human rights standards by athletes. It identifies a pattern of conduct in the structure of international sports that has implications for a wide range of rights at stake in sports, and it serves as a proclamation on wide human rights abuses in sports.

It is notable that transnational non-governmental sport entities are bound by international human rights law both within the framework of UN Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights and within the general framework of human rights treaties. In fact, States have an obligation to respect and implement the right to freedom of speech but at the same time “[t]he obligation also requires States parties to ensure that persons are protected from any acts by private persons or entities that would impair the enjoyment of the freedoms of opinion and expression”.

The restrictions on freedom of speech and expression and infringement of this right by non-State actors has been the subject of concern by the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Speech as well, who points out that “an increasing number of actions by non-State individuals and entities have a marked and severely negative impact on the enjoyment of those rights by others.”

Although the report mostly focuses on the role of armed groups, it also confirms that non-State actors can be responsible for violation of the right to freedom of speech. The Special Rapporteur calls the attention of the UN Human Rights Council and all governments to the actions of the non-State actors within their territory that rise to the level of “repression and intimidation”.

Sports governing bodies need to comply with international norms

Thus, athletes do have the right to freedom of speech on the field of play in all its forms especially if they are discussing human rights. Based on the above guidelines, a blanket ban by sport governing bodies on all types of speech, in particular those addressing human rights issues, is in contradiction with international human rights and the aim and purpose of the right to freedom of speech and expression as well.

The regulations of sports governing bodies do not have the status of law and at the same time sport organizations generally do not make clarifications on what constitutes a political gesture and instead tend to interpret all gestures as political and ban all types of speech.

Whether sport governing bodies, in particular those headquartered in the territory of States that are party to human rights treaties, are willing to make self-reforms and comply with international norms remains a question to be answered in the future. If the right to freedom of speech should be restricted for athletes and to what extent sport governing bodies can limit this freedom, it is up to a competent court of law to rule upon the legitimacy and legality of such regulations. Otherwise, the boundaries of the right to freedom of speech for athletes, is what the law designs and describes for other individuals within the society.

In fact, in the end, it is an individual who feels the pain of discrimination, racial insults, genocide, repression of political dissents, war, inequality, illness and corruption, and not the legal personality of organizations. Sport without a taste of humanity is as George Orwell wrote in his essay ‘The Sporting Spirit’: “a war without weapon!” What makes sports powerful is that when some humans are in pain and their human rights are violated, other people in key moments of their lives, during the match or on the podium, do care about them; they care about human suffering and they try to empower the voice of the unheard and marginalized communities.