Cricket gets smaller before it can grow?

More is the mantra for the number of teams at most sporting world cup finals with one major exception: cricket. This year’s Cricket World Cup in England and Wales features just 10 countries, which is four less than the 2015 tournament in Australia and New Zealand.

While all other major team sports are expanding, cricket continues to struggle with an arcane organisational structure which gives control of the game’s commercial income to a handful of big countries, who have shown little appetite to grow the game globally.

Most international federations have mainly full members and a small number of junior members, but the International Cricket Council (ICC) has just 12 full members and 93 associates. Despite a programme of expansion started in 1998, the status of this elite has always been protected.

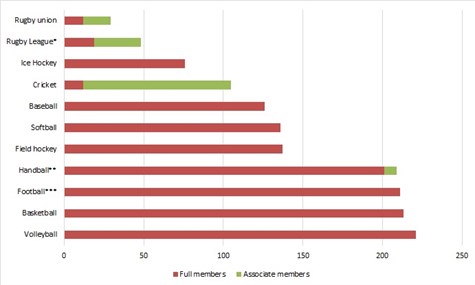

Figure 1. Full and associate members in various sports The figure shows the proportion of full and associate members in various sports.

The figure shows the proportion of full and associate members in various sports.

Note: The World Baseball & Softball Confederation (WSBC) affiliates baseball and softball associations

*Members of regional confederations

**Associate & regional members

***11 affiliate members, 17 observers

In 2011, after a series of corruption scandals the ICC commissioned a report into its governance by British barrister Lord Woolf, whose recommendations were mostly ignored. A year later, Transparency International published its own report, Strengthening Integrity and Transparency in Cricket, and urged the ICC to introduce greater ‘transparency, accountability and anti-corruption measures'.

“There has been some improvement at the ICC but most of what we wrote then is pertinent today,” says Robert Barrington, executive director of TI’s UK chapter. “Australia, England and India captured the board [in 2014] and seem to have rowed back on that which is good.”

This putsch by cricket’s three economic powerhouses aimed to capture the bulk of money from the 2015-2023 commercial rights cycle. After widespread protests, the plan was watered down but the World Cup was cut from 14 to 10 teams.

Other changes included abandoning the old three-tier system of membership. The bottom tier affiliates were third class in every sense.

Now, only associates ranked within the top 40 are deemed voting associate members. Those outside the top 40 – more than 60% of members – get to elect five regional representatives. The elite’s grip remains. Last year, Afghanistan and Ireland swelled the ranks of the full members to 12 and this elite now controls 75% of the voting power.

The long game

These 12 countries also get to play tests over five days, which is the sporting pinnacle of cricket. This format rarely generates much money outside of a handful of countries, such as England and Australia, and shorter formats that take only a day, such as this year’s one day (ODI) World Cup or the shorter format, T20, are more lucrative and being used to globalise the game.

The 32 leading members have been included in a new ICC pathway (see PDF) towards the 2023 ODI World Cup in India, but outside of the bigger full members, cricket rarely generates much money.

Global expansion costs the ICC money. With the appetite for expansion uncertain amongst the full members, the future for those small associates outside the new pathway is less clear.

Until last year, the ICC’s old T20 World Cricket League provided an opportunity to play internationally for associates as far apart as the Falkland Islands and the Seychelles, but this format has been dropped.

Instead, all T20 matches have international status and smaller associates are now being encouraged to play each other to generate points for a new global ranking.

Will Glenwright, head of global development at the ICC, says: “We are positioning T20 as the area for growth for the international game. Not many of our members [outside of the leading 32] play 50 over cricket.”

Previously, associate members paid a $10,000 participation fee to play in official ICC tournaments like the WCL. Now, that has also been scrapped but moving up cricket’s arcane membership structure to full membership status looks harder than ever.

Before Afghanistan and Ireland’s elevation last year, the last countries promoted to full membership were Bangladesh in 2000 and Zimbabwe in 1992.

Preparation for gaining test status came through four-day matches in the Inter Continental Cup, which since 2005 was won by either Afghanistan (twice) or Ireland (four times). Now the old Inter Continental Cup is gone too. An ICC spokesperson says: “There was an expressing of interest from a handful of ICC Members, and this is currently going through the process to see what a version of the ICC I-Cup may look like.”

For small associates such as Cricket Chile with annual funding of around $16,000, the choice between playing a format almost guaranteed to lose money, or spending their funds on development and playing T20 games is not difficult.

Performance or participation?

Cricket has wrestled with whether to focus on performance or participation for years. The emphasis fluctuated between rewarding members for the number of new players brought into the game and international performances on the pitch. As the ICC sought to increase its membership, this did not always benefit the game’s governance and credibility.

The ICC had 45 members until 1998, when a committee led by the South African Ali Bacher embarked on a huge expansion programme. Within a decade, membership had swelled to 104 countries but has since been virtually static.

Hungary and Russia joined in 2012. Saudi Arabia were upgraded from affiliate to associate member in 2016 but Cuba, Switzerland, Tonga and the USA were all expelled, while Turkey, Brunei, Morocco, Nepal and the Falklands were suspended.

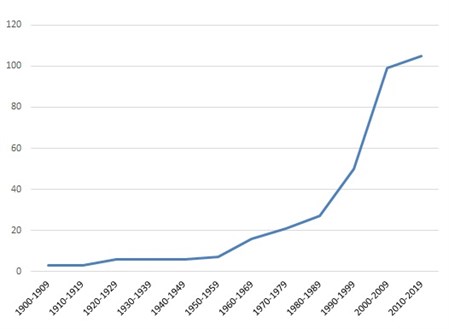

Figure 2. ICC memberships

The figure shows the number of ICC members (full and associate) from 1900-2019

Nepal were suspended for government interference, but poor governance has also been a problem. In 2011, the ICC suspended Malawi for ‘mismanagement and poor governance practices’ then reinstated the Africans three years later.

In other countries, cricket’s expansion was hindered by lack of state recognition.

Iran was made an ICC affiliate in 2003 but the sport was administered together with baseball and softball until 2010 when, a dedicated cricket association was created at the ICC’s behest. The ICC requested the same in Turkey. When this demand was not met, suspension followed.

Some members hardly active

According to the 2017/18 annual report, the ICC had 92 associates, but this includes the likes of Cameroon and Morocco, which have not played in official ICC international tournaments for years.

Solefack James, a cricket development officer in Cameroon and former national team captain, says that his country has not been invited to any ICC tournaments since playing in Division Three of the World Cricket League (WCL) Africa tournament. These bottom level tournaments were abandoned in places such as Africa and South America, which Glenwright admits was a “sore point”.

In some other countries, personnel running national federations have not been up to the task. Morocco’s last participation was at the same 2012 WCL Africa tournament. The ICC suspended Morocco in 2015 after numerous requests for key documentation including financial accounts were ignored.

Some smaller members were sometimes recognised by the ICC with unseemly haste. A national association was formed in the same year as securing ICC recognition in places as diverse as Bhutan, Cyprus, the Cook Islands, Gambia, Indonesia and Lesotho.

Growth pains

The rapid pace of change in both ushering in new members and attracting more players also proved problematic. By 2010, ICC membership had swelled to 106 countries. At its annual conference in Hong Kong in 2011, the ICC launched a new strategy called ‘A Bigger, better Global Game’ to ‘target more players, more fans, more competitive teams’.

In 2011, there was also a 24% rise in new players according to the ICC’s annual report and a target was set of attracting one million new players through associate and affiliate members by 2015. This was a growth rate of 23%.

In February 2012, the ICC Board approved the introduction of a US$12 million targeted assistance and performance programme to improve competitiveness amongst full members, leading associates and affiliates.

Off the field, members’ performance is measured using the Scorecard system, which uses 12 weighted criteria that cover off-field aspects of the member’s operations from participation to infrastructure and non-ICC income.

Tim Cutler, the former chief executive of Cricket Hong Kong, says: “All figures are self-reported. The harsh reality here is that a single place change in one ranking metric could result in a huge positive or negative effect on a member’s funding – unsurprisingly there have been reports of various instances of 'creative accounting'."

According to Cutler, now a consultant and founder of EmergingCricket.com, these cases often were dealt with privately, but examples range from the USA exaggerating the number of natural grass pitches to Surinam claiming to have 25,000 young players in one ICC return then using ineligible players to gain promotion from WCL Division 6 in 2015.

Still an expat game

The issue of eligibility remains crucial for cricket. While the game was initially spread by the British Empire in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, in many associate members the game has a foothold through immigrants from Asia, particularly India and Pakistan.

“If you took the Indians out of Chile tomorrow, we wouldn’t have a structure,” says Chilean cricket pioneer Chris Emmott.

The ICC’s eligibility rules mean that to play internationally, players need at least a grandparent or parent from the country they choose to represent or to have lived there for three years.

For some associates under pressure to get results to guarantee funding under the old criteria, the temptation to recruit ineligible players was hard to ignore. Surinam were not the only country to recruit ringers. Swaziland were also penalised in 2013 after using five Asian players, who had previously played for Mozambique.

More flexibility to lead growth says ICC

Despite almost US$1.8 billion being distributed over this current rights period (2015-23), smaller associates are struggling with a funding cut according to research last year by Dutch cricket journalist Bertus de Jong. This showed that associates will get around $160 million over eight years, which is down from $280 million in the last cycle.

Speaking this year, Will Glenwright says the ICC will spend more than $300 million on associates over the current rights cycle, but the onus is now on associates to help themselves.

Glenwright explains: “One of the weaknesses in our old system was that in order to play international cricket you had to play ICC tournaments. Now we have awarded T20i status to all our member federations and we are seeing an explosion in bilateral cricket.

“The Europeans have told us they can get funding from government if they are playing in an international tournament that provides ranking points. For some countries, how far up they move up a global ranking determines government funding. It’s creating an opportunity for more cricket to be played and creating funding.”

In May 2019, the ICC unveiled its first male T20i ranking with 80 countries listed, comprising 12 full members and 68 associates. Another 12 associates had played matches but did not have sufficient points to qualify. The same amount again had not played.

Although the cost of playing bilateral series now lies solely with associates, matches are emerging in Europe at least. In March, Spain hosted a triangular series with Hungary and Malta, while in May Belgium hosted Germany in a T20i series in Brussels.

Belgian Cricket Federation chairman Hassan Shah says: “The ICC pathway is much better now. It has increased the chances for associate members to grow and play at higher level. Also, the flexibility to host and play T20i has helped the associate members to attract local media, players and sports authorities.”

The reforms also gave meaning to existing series that were not recognised by the ICC. Chris Emmott adds: “This has opened up the eligibility. Before, we couldn’t attract the locals as we had a South American Championship that was not official but now they can come and play in a full international recognised by the ICC.”

Membership stalling

The global ranking will also help bring in sponsors says Charles Haba, a pioneer of cricket in Rwanda and former president of the national association. “It’s important to understand where the ICC is coming from. The sport is struggling with funding and identity.

“The best way to succeed is to provide the most popular game, which is T20. It’s difficult to persuade the big brands to support a game like cricket, which is only played by 12 or so countries.”

The elite has grown gradually, but the ICC’s appetite to grow the game appears to have withered. Membership has stalled as those countries expelled have exceeded the handful of new members. The last new member, the USA, was only being readmitted after the previous federation had been expelled.

Glenwright admits: “There’s a number of federations who have reached out to us. To be brutally honest, that’s not something we have been good at in the past.”

To overcome this, in 2016 the ICC started the Global Leaders Academy for new administrative staff and 122 people from 65 countries have passed through. Entry-level programmes to develop schools and train umpires in potential are being developed to help potential new members, which include Colombia, Congo Brazzaville, Egypt and Timor Leste.

For all the admirable efforts of the ICC’s development department, the game remains in the grip of an elite, whose appetite for growth is typified by cricket’s lack of interest in the Olympic movement.

T20 cricket was mooted to appear at the 2018 Asian Games and its omission was difficult for Asian associates, where state funding is partly tied to inclusion in the Games. The 2022 Asian Games in Hangzhou, China, will however feature cricket. If cricket is well received, the next logical step would be an attempt to join the Olympic Games.

Participation at an Olympics could surely not be restricted to a mere 10 countries and may help further globalise cricket, but only on the terms of the elite countries that generate the bulk of commercial income and at present appear to lack interest in the rest of the world.

Further reading: